After I had been a Bahá’í for some time, it occurred to me as I looked back over my life how there had been a gradual development and broadening of my perception of religion, from conservative and restricted beginnings to appreciating the similarities in different religions – and indeed, an understanding of how much very diverse people have in common. With my scientific background, the emphasis on reason and the exclusion of superstition from the Bahá’í teachings immediately resonated with me. Somehow, despite losing faith in my original religion, I retained a belief in God, and was particularly attracted to the Bahá’í teachings on ‘progressive revelation’.

This history is an attempt to show how this happened for me.

Growing up

I was brought up as a Roman Catholic, and attended St Joseph’s RC Primary School in Derby (since converted to a Sikh Temple) and then the local Convent Grammar School (St Philomena’s). Attending Mass every Sunday and having prayers at Assembly and before classes was ‘normal’, plus a week-long ‘retreat’ period at school each year where we held silence and attended special services. All of this gave me a sense of ease with religious practice, and with talking about religious matters. I felt quite committed and didn’t really have any doubts about my faith. I had a very idealistic view of the religion, seeing the Pope as a ‘benign dictator’. In those days Catholics were not encouraged to find out about other religions – they were never mentioned. Even to go into a church of another Christian denomination would have been counted as a sin. I was the sixth in a family of seven children. My parents were quite protective of us and we didn’t play much with other children, so you could say that I had a sheltered childhood.

As a teenager, I began to question what I had been taught about religion. In the convent school, they never told us anything negative about the Catholic Church. We had no idea about the activities of some of the medieval popes. And something they were very particular about was that we mustn’t go into any other places of worship. At that time, I didn’t know about other religions, but I did know that some people were Protestants and I wasn’t to visit their churches. There were only one or two non-Catholics at the convent school.

But in the Sixth Form, in the late 1960s, we were beginning to discuss things and question, and form our own opinions. I heard about some of the not-so-good things that had happened in the history of the Catholic Church. The world was changing: there were books coming out giving alternative views on religion (one such was the ‘prophecies’ of Nostradamus); different attitudes were expressed in the satire on TV. There was a flowering of pop music culture and an explosion in the variety of clothing styles available. A rebellion of youth: conventions were flaunted, institutions were questioned. It was very much a time of ‘Peace and Love’ for all, and finding a Guru to follow, or trying out meditation or yoga. I well remember a feeling that all was right with the world: young people were rejecting the outworn habits of their parents’ generation.

Somehow I held on to my belief in God, even through the ‘70s when books started appearing disputing the existence of Jesus as a historical figure, and the feeling that ‘God is dead’ was gaining currency. It must be that despite having been taught about the Trinity, I never quite believed that Jesus was also God – so I could take on board that He might never have existed.

When I left Convent school in 1970, I was becoming disenchanted with Catholicism. The sermons preached each Sunday seemed irrelevant, unrelated to real life; the dogmas were wearing thin, permitting as they did, no questions. I soon dropped out of active Christianity as I followed my degree course, and fell away from going to church every Sunday. Religion became irrelevant to my life; and I was beginning to meet people from other faith backgrounds.

Learning about other religions

At university in Leicester I had an Israeli Jewish boyfriend for a while. He met my family, but they were rather disapproving and that was when I realised they were rather xenophobic. He had gone through the Six Day War and told me about how he had some Arab friends and they were now on different sides – so I was beginning to learn about religious conflict. I could see that although this boy was very attractive and fond of me, the relationship wasn’t going to go anywhere as we were too different culturally. Also, I could tell that his mother was a bit disapproving of me, and didn’t want an English Christian wife for her son. This was my first encounter with someone from a different religion and a different culture, which helped me realise that we could get on very well and that we shared many of the same values.

I stayed on at university to complete a PhD in science, meanwhile falling in love – for both of us, it was the first serious relationship. We moved in together and I felt I should be honest with my parents so I told them about this. They were very disappointed. Although my boyfriend didn’t actually ask me to marry him, I felt that it was a possibility, so I enquired of the parish priest back home whether we would be able to marry in the church. I told him we were living together and that my boyfriend wasn’t a Catholic. The priest told me “yes you could, but you would have to stop sleeping together and you would have to confess it as a sin”. He said it was fornication. To me, it didn’t feel like a sin, because we were both free to be together, no one else was getting hurt and it seemed a very natural thing to do. I talked this over with my parents, and at this point I realised that I couldn’t belong to the Catholic Church any more as there are rules I would have to live by, and I didn’t want to be a hypocrite.

I went away from religion at this point, and having a full and busy life at that time, I didn’t feel the lack of a spiritual life.

My boyfriend – later my husband – didn’t like to talk about religion. He had a cynical view of the Catholic Church, but although I had left the Church behind, I still felt that it had a positive influence in the world.

We moved from Leicester to Nottingham in 1977. When we moved to Nottingham, we told our new landlady that we were “engaged” and she told us we really should be married before we could move into the flat, so we married then, in a very low-key registry office ceremony with just our parents there. We shared our flat with a third person, and when they moved out, a young man moved in who was a Muslim. We noticed that he was doing his ablutions every morning. One evening as we were eating, he came in and my husband invited him to join us in our meal. Our flatmate said “I will join you, because Muslims are allowed to eat with ‘People of the Book’”. I had never heard that term before. He had assumed we were Christians. That made me think, because I didn’t know that other religions had rules around who their members could mix with. I had never before come across prejudice against other religions from non-Christians. In this case, the prejudice was against Hindus (regarded by this Muslim as pagans).

After Nottingham, I got a job at Birmingham University and we moved there in 1978, as I pursued my career as a research scientist. Along the way I met people who made me think again about religion. I joined a silversmithing evening class where I made friends with a Hindu lady. She told me the story of Krishna which seemed to me similar in parts to the story of Jesus. At this time I was still thinking of these as stories, as I didn’t feel that I believed. But we got on well together, and this was how I came to realise that I could find a lot in common with people with other beliefs.

I also learned something of the Hare Krishna movement; there was a great feeling of optimism among the young. As we saw and heard of peace movements across the world, there was a feeling that young people could put things right in a world messed up by our elders, who we held responsible for wars and the state of the natural world. Luckily I was not drawn into the destructive experimentation with mind-altering drugs which was eventually to turn this era sour.

As I left my twenties, I became more and more aware of an empty space in my life. With hindsight, I would say I was becoming a ‘seeker’, looking for ‘something else’.

In 1981, my research coordinator was moving to the University of Bath to take up a chair, and he invited me to join his research team there. That was lovely for me; I had never been to Bath before and thought it was a beautiful city. Each time I moved to a new job, my husband followed.

It was in the early 1980s in Bath that I came across the Bahá’í Faith for the first time: in 1983, a young Bahá’í girl in Iran named Mona was executed for her faith, along with nine other women. The story was widely publicised in the UK and I read an article in a newspaper about this execution and what Bahá’ís believe. I remember thinking “this all seems very sensible” but didn’t take it any further. Around this time I saw some people standing somewhere in the city, publicising an event connected with this. But again I didn’t take it any further or make any enquiries.

I was now 30, my friends were having babies and I started to think the time was right for us to have a baby – and our son was born when I was 33. My research contract was coming to an end, because the professor I was working for was applying for new funding and as I got older, I was becoming more expensive! I didn’t want a permanent lectureship, so this was going to be the end of my research career. But my professor told me that a job was being advertised in Western Samoa, at the University of the South Pacific. My husband agreed that if I got the job, he would come with me and look after our young child while I was working (he wouldn’t have been allowed to work in that country). I applied, and was pleased but quite shocked to hear that I had landed the job, setting up a plant tissue culture laboratory at the School of Agriculture, Alafua Campus.

I would not have applied for this job on my own – it was important that we were going as a family. And it was in Samoa that I met the Bahá’í Faith.

Western Samoa

I was still in a daze when we set off in early 1985. Our young son was just over a year old. This was well before the days of the information explosion, and I recall that all we could find out about Western Samoa was based on a very dark, black and white photocopied article from a National Geographic magazine. We had so little information, we hardly knew what to take with us. I remember my excitement, but also a feeling of “who will we find to be friends with?”. But it is funny how certain parts of the world appeal to you: one of my favourite books when I was young was The Coral Island by R M Ballantyne. It described things like breadfruit growing. I found the idea of a tropical island with exotic fruits very appealing. This predisposed me to want to go to that part of the world.

We landed in Samoa, and these were my first impressions: feeling the tropical heat surrounding us, bewildered by the new culture, the greenery, the lack of ‘proper’ houses, the men and women wearing lava-lavas in clashing colours, the new smells and sounds, and so many children everywhere. There was only one metalled road, and you couldn’t really tell where the town started and ended; the traditional houses or fales were mainly platformed, with thatched roofs and open sides, and lots of tropical greenery everywhere around. After a first night in a hotel, we were given a prefabricated house, fairly basic by European standards but with mod cons such as a fridge and washing machine that were not available to most Samoans. We learned to find our way around; we found that our pushchair didn’t work, because of the gravel roads and paths.

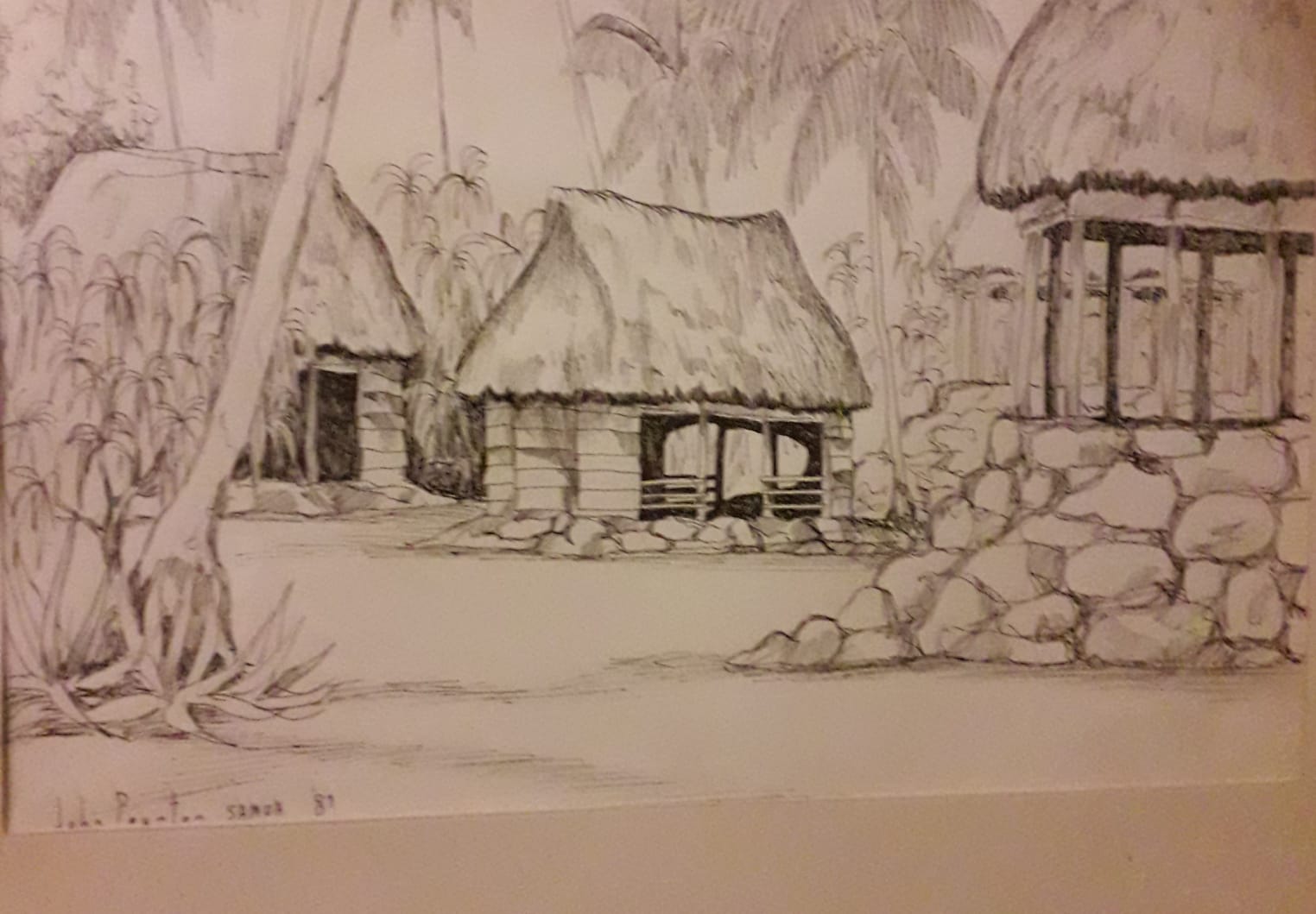

Sketch of a traditional ‘fale’ by a local artist

One of the first things we noticed was this amazing building which was the Bahá’í House of Worship. It looked totally different from all the other buildings around. It was off one of the main roads leading to a beach that was popular with falangis (foreigners). You couldn’t miss it, as it stood out from the local traditional fales and the new prefabs which were beginning to be imported from New Zealand.

My job was to set up a laboratory on the island. The main campus of the University of the South Pacific was on Fiji, about a two-hour flight away. The students came from all over the South Pacific, which was very interesting and there would be cultural events where they all showed off their own cultures, and you could see how it was ‘the same but different’ in the different islands: different dances, different weaving styles, and so on.

Woven basket from Tonga

Woven fan from Tonga

This was to be a truly life-changing experience for me. I learned that people are the same the world over, and so it is easy to make friends wherever you are. I also realised that something with the same basic materials and techniques – such as the weaving arts – could be taken forward and refined without losing their essential substance. And this resonated with me when I began to learn about the Bahá’í teaching of progressive revelation.

Being newcomers to a small island, of course it was we who were noticed. Before long, my husband was approached by Cecily Trent, the very English lady running the newly set up Montessori School next door to the House of Worship. At that time there was only one shop in town with air-conditioning, and this also had a café where all the falangis would gather to escape the heat. I was at work (no air-conditioning there) and my husband was looking after our son. He would go to the shop to cool off and enjoy a cold drink, and here he met Cecily. Cecily told him about the Montessori school, our child being almost of the right age to start attending. And this was a great start to his education.

Cecily also held Wednesday evening meetings, called ‘firesides’, in her apartment next to the Montessori School, and invited us to go along. We started going to the firesides every Wednesday, leaving our son in the care of a local woman who was related to our landlord. Cecily always made a boiled fruit cake, and thinly cut cucumber sandwiches with the crusts removed. Despite the prevailing dusty pathways, her house was immaculately furnished in white, in a very British style. She was a larger-than-life, faintly aristocratic character, with uncompromising views, yet somehow endearing. She was carefully turned-out, with beautifully coiffured hair and make-up. She would wear a kaftan and looked somewhat regal.

Cecily started every fireside with an overview of the basic facts of the Bahá’í Faith, and then just allowed us to lead the conversation wherever it went. The other main participant was an educationalist from India who followed Krishnamurthy, so we explored some very interesting subjects. I really felt that I had been put in a place where I couldn’t ignore this new religion I was hearing about. To me it was a tremendous boost, and I realised that this was what I had been missing: the spiritual side of life. The experience woke me up. Cecily had an extensive library and I read all kinds of Bahá’í books. I read and read, and questioned, and read more, and questioned more. I found the stories of the main figures of the Faith culturally remote and hard to relate to, though I very readily accepted all the principles. I attended the firesides for the whole of the two years I was on the island.

Only very occasionally did we meet other members of the Bahá’í community. Cecily must have been part of a community, but she did not go out of her way to introduce us to other Bahá’ís. We were invited to a few occasions in the House of Worship. King Malietoa Tanumafili II attended these events, but it wasn’t made very public that he was a Bahá’í, and I didn’t know this at the time.

I found out later, on returning to the UK and meeting Susie Howard and Sarah Richards, that Cecily Trent was their aunt. She had introduced their mother, Atherton Parsons, to the Bahá’í Faith. Cecily had travelled widely and is buried in Tonga.

My husband met Joy Percival, who had a young child about the same age as our son. It was not easy for him socially, as a man looking after a child while his wife worked. Joy was from New Zealand and through her and her son, we met her husband Stephen Percival. He and Joy used to call over and visit us, and in the course of conversation we could see he was looking at things a different way. He would often say things which would intrigue us. He didn’t introduce himself as a Bahá’í, but I became aware of this later. Stephen was half-Samoan and had been educated in New Zealand, where he and Joy met.

There was only one occasion when we went along to what was called a feast, though we didn’t really know what that was. Someone was speaking there – it was Mr Soheil Alaee, who was a Counsellor (though we didn’t know it at the time). There were quite a few glamorous-looking people there, many of them Persians. At a certain point in the Feast, my husband and I were asked to leave the room. We wondered what was going on.

We had the impression that there weren’t very many Samoan Bahá’ís. The way it worked was that a whole village would belong to the same religion, usually one brought in by earlier missionaries. To become a Bahá’í would distance you from your village. Unless the Chief became a Bahá’í, in which case the whole village would be Bahá’í. We only knew of one Bahá’í village, which we never visited.

One time we visited a Christian village. We were invited to their church service, and were embarrassed when, after the collection had been taken, the pastor announced how much money had been collected from different people. We felt uncomfortable as we realised we would have been expected to contribute generously. Westerners were perceived as people with money, and this was something we weren’t used to. We had modern appliances, especially cars, that local people aspired to owning.

A car was necessary – walking was unsafe for falangis, because all the houses had fierce-looking dogs. I never really felt unsafe, although we did experience an armed robbery at a neighbour’s house while we were there. My husband always wore a shirt and tie, with trousers (not shorts) despite the tropical weather. When we heard shots being fired one evening, he rushed out to help and the intruder ran away. Perhaps he was impressed with my husband’s formal dress and thought he was a minister or someone else important. Tall and thin, he looked very like the portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson in one of the island’s two hotels. (R L Stevenson is buried on the island.) Perhaps this also helped to protect us from harm! Incidents like this made me realise that we couldn’t rely on easy access to local police etc in an emergency.

On the island, we tended to socialise within our cultural groups. I was working with someone who was a Fijian from a Scots background. His parents (or grandparents) had first settled in Fiji to run a sugar plantation, and his wife was from Palau. We mixed with this couple and others from New Zealand. Some of these people had children of our son’s age and he would spend time with them. Another couple had met and married through the Unification Church (then known as ‘Moonies’). They were friendly and sincere, and told me about the many good teachings of their church, which contrasted to the bad publicity that this church was getting at the time. For me, this was another example of the commonality between religions.

My husband hadn’t been able to work in Samoa, and after a home leave visit, he stayed in the UK and I came back to Samoa alone with our son Mark, now aged three. Luckily for me, Mark felt at home there and was happy to go back. I had help with looking after Mark while I was at work, and I continued to attend the firesides. I had plenty of time for reading the many Bahá’í books that Cecily had lent me. As I was now a woman on my own, a Samoan man – the husband of the babysitter – used to sleep on the verandah of our house, by arrangement with the landlord. I never felt unsafe but this was evidently considered the right thing. Socially, it was going to be difficult for me to stay there on my own for any length of time. I stayed on for another six months while someone else was found to take my place at work.

One of the ‘seekers’ at the weekly firesides, Wendy, had told me that if I wasn’t sure whether to commit myself to my new-found faith, the thing to do was just to live with it for a time. So I did this for the next couple of years, including after my return to the UK. I kept my mind open, but I never found anything that was more meaningful to me than the Bahá’í teachings.

By the time I left Western Samoa, in late 1988, I was more and more convinced of the truth of the Bahá’i teachings, but could not believe such a religion could be found in England. Cecily had told me that I would be sure to find a contact in the local telephone directory – and so I did!

My Baha’i life in England

When I came back to England, I was surprised to find a small Bahá’í community in Bath. I had still to pass my UK driving test, and I learned that my driving instructor was a Bahá’í.

Eventually, and after my marriage had unfortunately broken up, I declared as a Bahá’í.

I was invited to a women’s meeting, where I met other members of the local Bahá’í community. And it was at this meeting that I decided to declare my faith in Bahá’u’lláh and joined the Bahá’í community of Bath in 1990.

Summer Schools

The first Summer School I attended, as a very new Bahá’í, was at Wellington in 1990. Although I went with other members of the Bath community, I felt as if I didn’t know anyone, yet by the end of the week had been made to feel so welcome, had so many interesting conversations (often in the dinner queue) and been inspired by the speakers. I loved the whole experience so much, that when Sally and Derek Dacey proposed organising a Summer School in the South West the following year, I eagerly joined the team as Registrar, with Jan and Hugh Fixsen. For five years we organised the Warminster Summer Schools and then the first couple of Sidcot Summer Schools. It was a wonderful – though exhausting – way to get to know the wider community from all over the UK. It was inspiring to work with so many others who were sincerely trying their best to apply the Bahá’í teachings to the many difficulties and logistical conundrums of organising a Summer School, and do it all with love and good humour.

Pilgrimage

I first went on a 3-day visit to Haifa in 1991, leaving behind my small son in the care of Bahá’í friends. As we waited to board the El Al flight at Heathrow we saw sniffer dogs inspecting the departure area and lounge, and underwent two hours of questioning. This was not long after terrorist attacks, and women travelling on their own were regarded with suspicion. In addition, of course I answered ‘yes’ to queries about whether I knew persons of middle-Eastern origin. I finally remembered I had a letter of invitation to go to Haifa from the NSA – and of course, no problem after producing that! On arrival in Tel Aviv, more questioning and searching of luggage, and then off we went to find our way to Haifa by train. I was struck by the sight of military personnel riding on buses or walking about the streets carrying heavy rifles, and the signs of much damage to buildings from past warfare. In Haifa, the Bahá’i development and surrounding gardens (the terraces at an early stage of construction) stood out as an area of beauty and tranquillity.

The spirit of love in the Bahá’i visitors (most of them on pilgrimage) who I mingled with was infectious. By the time I left to go traveling to Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee, it was hard not to “regard all men as brothers”, and to forget that in the holy Land there were definitely two separate nations who regarded each other with suspicion. Luckily I was travelling with Mahin Humphrey who had lived at the World Centre for many years, and knew her way around, and when to be cautious.

All too soon we were back at the airport, chatting with new-found friends from many different countries as we waited for our flights home.

In the Bath Community

Being part of a small community, I was elected to the Local Spiritual Assembly within a few years of declaring. I sat on the Bath & N E Somerset SACRE (Standing Advisory Council for Religious Education) when it was set up in the early 1990s, and have been on that committee ever since, latterly as Chair for several years. Through my SACRE contacts, I had the opportunity to give a two-hour lecture on the Bahá’í Faith to students on the Study of Religion course at Bath Spa University for several years. This opportunity came as I had earlier completed postgraduate teacher training, and had taught for long enough to get my registration as a science teacher – although I did not stay in the profession long.

About the same time as I became a Bahá’í, following the direction of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to “consort with the followers of all religions in a spirit of friendliness and fellowship”, I became a member of the Bath Interfaith Group committee, as Treasurer, and later as Secretary for many years and still continuing in this role. This has led to many opportunities to talk about the Faith and to work in fellowship with those of other religions. I have remained involved with the interfaith group for over thirty years. One of my personal highlights was a meeting I arranged [date] at which local representatives of six other religions and the Bahá’í Faith spoke on the “Oneness of God” – all in accord, which was remarkable for the time.

I joined the Bahá’í community at a time when there was a strong local community in Bath with people of all ages, and many activities to help with. In those days we did not have systematic teaching and Ruhi books, and mostly gave fireside and public talks, and lots of cooking was involved! Through these efforts, our little community became known locally, especially through interfaith activities. The size of the community waxed and waned as people passed through, but nobody new joined from the locality.

As we waited for “Entry by Troops” before the millennium, our community had the experience of more than one visiting Bahá’í passing away suddenly, and therefore requiring local Bahá’í burial. Bath Spiritual Assembly decided to investigate whether we could use part of Haycombe Cemetery for Bahá’í burials, so a couple of us visited the cemetery superintendent and were delighted to learn that they could allocate a section for this purpose. Over the years, several of the Bahá’í community have passed away and been interred there, and I am proud to have played a part in getting the Bahá’í burial site established.

Looking back over the years, the most important thing in my life seems to be the way circumstances put me in a position where I couldn’t escape meeting the Bahá’í Faith, on a small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Jane O’Hara

Bath, April 2024