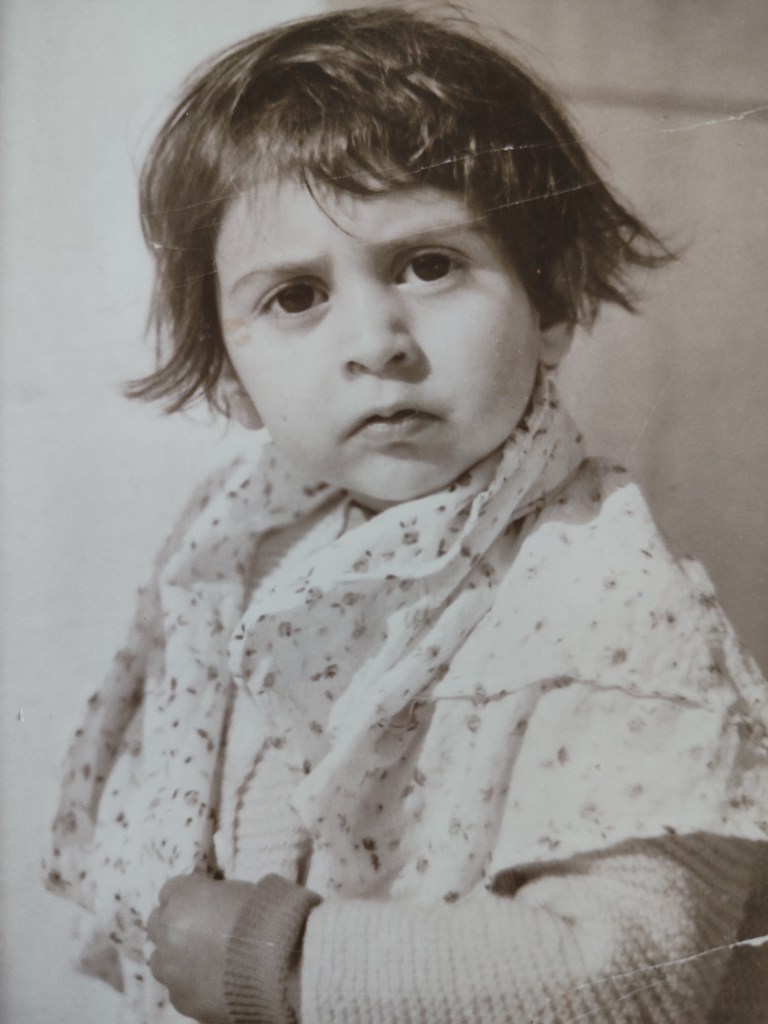

Childhood

I was raised in Tehran with my parents, a brother ten years my senior, and a half-brother twenty-five years older. While my mother Náhíd didn’t attend university, she had a passion for learning and took classes in English. My father `Alí-Akbar studied agricultural engineering, was fluent in Turkish and spoke English and French, and was a successful businessman.

I later discovered that I was born in the Bahá’í Missaghieh hospital, delivered by a Bahá’í doctor, and grew up near the district where the holy family lived.

Our family enjoyed a comfortable, westernised lifestyle. Although nominally Shia Muslim, my parents prioritised virtues over strict religious observance.

Both my brother and I attended an Armenian primary school, where English was taught as a second language. I continued my education at the International School of Tehran: Iranzamin.

Life, Death, and Elvis

My journey towards exploring my spiritual identity began when I was just five. It was a tragic event – the sudden death of my half-brother while we were on holiday at the Caspian Sea. I vividly remember the moment when he was brought ashore, and my father cleaned his face. It was my first encounter with death. I started questioning the meaning of life, contemplating where he had gone and why.

I reasoned that if God existed, He must be around us rather than distant in the heavens or the clouds!

Another significant event was the death of Elvis Presley in August 1977 when I was twelve years old. It stirred up spiritual questions within me. I had a dream about Elvis, which further fuelled my interest in spirituality.

Revolution and Imprisonment

In 1981, when I just turned sixteen, our lives took a dramatic turn.

The Revolutionary Guards stormed into our home in the dead of night, brandishing guns. They accused me of being part of a leftist underground movement, a claim that held no truth. They took all three of us – my parents and me – into custody.

It was a terrifying ordeal.

As we were escorted into the car, my mother caught sight of the son of our cook among the guards.

We suspected he may have tipped off the authorities about my father’s prominent commercial connections; my supposed political affiliations merely a facade to mask their true motives.

Sitting in the car my father leaned in close and cautioned me to be careful about what I said and that the alcohol in our home was not ours! Like many liberal Persians of the 1970s, my father indulged in occasional drinking. I met his gaze with defiance. “I won’t lie about anything,”.

Looking back, I realise that my words may not have been the most reassuring choice, especially considering our destination – one of the most notorious prisons in the world: Evin.

We were separated into different cells, isolated from each other and subjected to constant interrogations. The guards treated us with suspicion, branding us as enemies of the state.

For three long months I languished in confinement, cut off from the outside world. Initially, I was in solitary. The cell was bare, with nothing but a cold, hard floor to sleep on. I was later moved to a communal cell occupied by other young girls and women who were prisoners of conscience.

Interrogations were frequent, and the guards showed no mercy.

I vividly recall a haunting scene that remains etched in my memory. It was the sight of a young girl, her legs swollen from torture, lying on the floor in a state of utter shock, agony, and exhaustion.

During those dark days, I found solace in prayer. Though I wasn’t particularly devout before, I turned to prayer as a source of strength. There was a lot of time for reflection and it was a way to find hope amidst the despair.

Meanwhile, my family endured their own trials. My father, a once strong and proud man, returned home a mere shadow of his former self. The ordeal had taken a heavy toll on him, both physically and mentally. He was a broken man, haunted by the trauma of his imprisonment.

I suspect they had kept me in Evin as a useful pawn during my father’s interrogations.

The turmoil and uncertainty didn’t end with our release from prison. My father faced further detainment, a cruel twist that left my family reeling. Despite his pleas and protests, he found himself back behind bars, ensnared in the web of persecution.

Fleeing my Home

For my mother and me, the prospect of staying in Iran was unbearable. The constant threat of arrest loomed over us. With our family fractured and our future uncertain, we made the difficult decision to flee the country.

In June 1983, my mother and I boarded a plane bound for Italy seeking refuge from the turmoil that had engulfed our homeland. We found sanctuary in Milan where my uncle provided us with shelter.

Eventually we were granted permission to join our family in the UK. By August 1983, we had made the journey across borders and were reunited with my brother who lived in Bournemouth.

Our joy was tempered by the absence of my father, who remained behind in Iran. It would be years before he could join us.

After moving to London to pursue my studies, there was a deeper longing within me that remained unfulfilled. I read the Quran in both English and Persian, but still felt a sense of spiritual emptiness. I joined the Jewish Society at LSE and even contemplated moving to a kibbutz. The holy land was somehow always a dream destination for me!

Little did I know that I would visit the holy land one day, but under very different circumstances.

Wayfarer on the Path

My journey towards embracing the Faith began with a chance encounter. It was not until I met a Persian boy in his early 20s that I was introduced to the Faith when I was eighteen, albeit indirectly.

Initially, I had no idea about his religious background. We met casually at a social event, and I was drawn to him but puzzled by his reticence about his faith. Despite our interactions, he never disclosed his religion.

It wasn’t until I attended a wedding of his relative and saw references to the Bahá’í Faith that I began to piece things together. Confused and curious, I sought answers from those around me, including his friends and my own family.

My mother shared some insights based on her limited understanding of the Faith; she recalled how local Bahá’ís had shown kindness to her during her childhood, and she mentioned that her boss was a reputable man who happened to be a Bahá’í, but I was still left with many questions.

Upon reflection, I grasped the gravity of the situation for Persian Bahá’ís. The atmosphere was tense and uncertain, explaining the hesitation in actively teaching a girl like me, recently arrived from Iran.

Frustrated by the secrecy and eager to understand his beliefs, I took matters into my own hands. I contacted the National Spiritual Assembly, and they sent me the Iqán and a prayer book. Whilst the Iqán was difficult for me to fully grasp, I felt a deep connection reading the prayers.

Guided by a Knight

Eventually, my friend extended invitations for me to attend firesides, which provided a platform for me to ask questions and learn more about the Faith.

I visited Rutland Gate out of curiosity and the Guardian’s resting-place.

The Bahá’í teachings resonated with me deeply, offering a sense of clarity and purpose that I had long been seeking. Yet, the thought of taking such a significant step by committing myself and its implications weighed heavily on my mind. My father, though resentful of how religion was manipulated, would never have supported rejecting Islam.

In late 1989, I attended a talk in London given by the Knight of Bahá’u’lláh Mehrangiz Munsiff. While I don’t remember the specifics of her speech, I do recall posing a question about some pedantic aspect of the Faith. Mrs Munsiff’s swift response of “it doesn’t matter” resonated deeply.

Following the talk, Mrs Munsiff approached me privately and inquired why I hadn’t yet declared. “Do you believe in Bahá’u’lláh?” she asked. I replied, “Yes, I do.”

As Mrs Munsiff extended the invitation to sign the declaration card, I hesitated, acutely aware of the potential repercussions. The fear of my father’s disapproval and the anguish it would cause my mother loomed large in my mind. How could I embark on this path without their blessing?

But Mrs Munsiff’s words carried a gentle reassurance. “Don’t tell them,” she urged, her voice a beacon of encouragement.

In that moment, a flicker of resolve ignited within me, especially when I was reassured that I will not be questioning my belief in Islam but reinforcing it by accepting the Faith. I reached for the pen and affixed my signature to the card.

I recall the joyous eruption within the gathering as I declared.

Ironically, it was my father who drove me to the gathering assuming it was an academic conference. He’d always been my source of inspiration, instilling in me a belief in something beyond the material world.

Reflections

In my journey towards embracing the Faith, many played a significant role. While there were families who radiated love, there wasn’t someone who explicitly took on the role of a teacher or mentor guiding me through the intricacies of the Faith.

My journey was shaped by my own experiences, interactions, and service. I wasn’t formally deepened about the Faith in a structured manner, but rather, I absorbed its teachings and principles through osmosis, so to speak.

With the political turmoil of the 1980s and 1990s, my official enrolment was delayed until June 1991. I was interviewed by the National Assembly about why I wanted to declare. By that time, I was engaged to Behnam who was a Bahá’í and we married in November 1991. The marriage provided me with more freedom to practice my new faith and I plunged into work on various committees and the Local Spiritual Assembly of Wandsworth. My two daughters Romina and Ariana are both active Bahá’ís.

I fulfilled my heart’s desire to visit the holy land by embarking on a three-day pilgrimage in 2001, followed by nine-day pilgrimages in 2006 and 2016.

While I never told my parents of my conversion, they might have sensed a change in me over time. We shared prayers and engaged in deep spiritual conversations.

After their passing, I had a dream in which my mother affirmed the truth of the Faith, followed by another dream where they both appeared in the presence of `Abdu’l-Bahá.

Mariam Partovi Fallah

Ridván 181 BE