Part One of Garry’s story deals with his childhood and youth. Further instalments to follow. – Ed.

Growing up

My family consisted of my parents Michael and Jane, and my three sisters: two older, Sally born 1946 and Virginia born 1947, and my younger sister Catherine, born in 1951.

I was born in Loughside, my parents’ house, on 29 April 1949, and we lived on the town land of Greenisland on the shores of Belfast Lough, near Carrickfergus in Northern Ireland

My mother accepted the station of Bahá’u’lláh in 1953 [1]. All my sisters registered themselves as Bahá’ís when they reached the Bahá’í age of maturity at 15.

I formally signed my Bahá’í declaration card during my 23rd year in February 1972 in Dublin, Eire.

I was about two years old when my mother first chanced upon the existence of the Bahá’í Faith. Her source was a book review in the local Belfast paper of one of George Townsend’s publications. The review excited her imagination. Living, as she was, in a land unsettled by religious conflict, the idea of the unity of religions struck a chord. It was only after another chance meeting with Ursula Newman, a Bahá’í pioneer living in Belfast, that she became an active enquirer.

One day, some two years later, after much thoughtful conversation with George Townsend, Ursula Newman, Adib Tahirzadeh and others, my mother decided finally to make a decision. Her question was this: Is Baha’u’llah really the return of Jesus the Christ? With sound spiritual logic she took her heart question to our local church and prayed to Jesus for guidance. While kneeling and praying at the altar in that empty local church she had the sensation of been lifted off the ground. She took this as a sign of affirmation.

My mother was nothing if not whole-hearted about her beliefs. She embraced the spirit and practice of her new faith with a total commitment. She adapted her life and ours in accordance with her new understandings. The destiny of our family changed for ever.

The reaction of her Anglo-Irish friends was shock and disbelief. How could a good person have ‘broken ranks’? A deep sympathy went out to my father. “Poor Michael” was the refrain. The reaction of our local vicar to my mother’s new faith came in the form of a badly researched and poorly constructed attack on the Bahá’í Faith. It was duly published in the Church of Ireland Gazette. It contained so many statements that my father knew to be false that it both shocked him and shook his own faith. It caused him to fundamentally question his relationship with Christianity. His conclusion was radically different from my mother’s. He came to the view that Christianity was fundamentally wrong; wrong in terms of the God it projected, wrong in terms of its morality and, on balance, negative in its influence on human life and society. He became a free thinker, and a confirmed atheist. He found best expression of his new world view through the Belfast Humanist Association. He also started working with and promoting an organisation called War on Want. War on Want raised money for good causes in third world countries.

My father was of ‘a good family’. He was a Royal Navy officer, a war hero and a company director. He was also a patron of the local church, church warden and regular churchgoer. He was seen as solid and conventional. My mum, with her privileged Anglo-Irish Protestant landowning ascendancy background, was a stalwart and respected member of our local Church of Ireland congregation. It was hence quite a moment when both these respected people resigned from the church. For them it must have been a big turning point. Two souls left the relatively unchallenging comfort of their conventional social settings and set off on their own, seemingly different but, as it turned out, strangely united paths.

So how did this all play out in terms of our family life?

Well, it bought to our relatively privileged but slightly down at heel, eccentric, chaotic Anglo- Irish household yet another layer of eccentricity!

Life must have already have been busy ..

My father ran a factory (extracting nicotine from tobacco), kept pigs, maintained a large vegetable garden and was passionate about the sea, sailing and his old boat which he kept moored off our house on the shores of Belfast Lough. My mother was preoccupied with settling in to their new house. She brought a highly conscientious determination to bring up her four children in the best way possible. However, domesticity was not one of her strong points. For her the matter of trying to keep the complexities of home life from descending into even deeper levels of chaos was deeply challenging! Even with the help of Nana, our Catholic live-in nanny, the gardener, the Protestant cleaners, and various au pairs, it was a full-time, demanding and not always successful endeavour!

So championing the Bahá’í faith and humanism must have added further complications to an already full life. But for me, as a four year old, it was the world as I knew it and the stuff of normality. For them it was definitely new cultural terrain.

There was nothing insular about our pre Bahá’í family. My parents’ world views were shaped by their relatively privileged landed gentry backgrounds in the context of the British Empire. As a debutante my mother had been presented to the King at Court in the 1930’s. My father’s family had a long aristocratic but not always conventional lineage. His great grandfather was one of Ireland’s richest landowners, an idealist who had championed Catholic emancipation. His grandfather had been commissioned in the Austrian and English armies, taken holy orders as an ordained Church of England vicar (which he practised for 20 years of his life) and then became an MP, an author and a published Egyptologist. As MP and landowner he championed the rights of agricultural labourers.

My father’s father sought his fortune in America and married an American lady before returning to Ireland. My father was born in America. In his early life he had been looked after by his black American nanny. My uncles and aunts had lived and given birth to their children in various Empire outposts, including India. My father and mother had travelled to East Africa after the war to investigate setting up a nicotine business. We were a hospitable household. Members of our wider families would visit; uncles, aunts, and great aunts from Ireland, Scotland and England. Cousins came, who lived in exotic places like Morocco, Spain and the Arabian peninsula. All carried tales of the wider world. With the Bahá’í Faith and Humanism came a further broadening of our social and cultural world. We began hosting people from a wider range of social and cultural backgrounds. My father brought free thinkers, humanists and War on Want people to our home. My mother made our house hospitable to all Bahá’ís. Of the local Bahá’ís, some were exotic, some eccentric and some were definitely of the lower orders! In that class-ridden scoiety, we would not have normally have mixed with any of them. In all it was a wonderful, exotic mix. Bahá’ís from Persia, Africa, the South Seas, England and Ireland were all given an equal and warm welcome!

Given all this, my mother’s Bahá’íness, rather than introducing a sense of cultural dislocation to our household, brought a new enriching dimension. Our empire cultural heritage was given a new depth by a spirituality that promoted the idea of one reality, one people, one earth and the beauty of human diversity. In my mother’s mind the notion of the British Commonwealth morphed into the expanded idea of a spiritual world commonwealth. At points of social concern my father’s social humanism chimed with my mother’s Bahá’í humanism. Despite their very different world views, my parents seemed to find ways to accommodate each other’s different paths. Despite their individual passions, and endless differences of opinion coming from diametrically opposite world views, I experienced their exchanges not as heated ideological dissonance or egocentric point-scoring but as an on-going debate that searched for reality. For me, old religion and new religion, theism and atheism, Catholic and Protestant, all seemed to live happily in our household. In that sense our family modelled a flowing dynamic of unity in diversity. As I remember it, we still went to church and Sunday school. We said the same kind of prayers at bedtime, with lots of God blesses (Mummy, Daddy, sisters, pets and so on). We still got Christmas stockings and celebrated Christmas with enthusiasm. I sometimes went to Mass with my Nana. There were no contradictions in all this, it was just what happened.

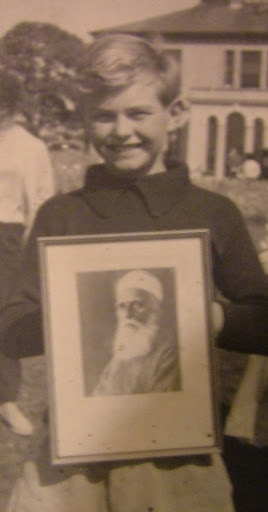

In the same way, my mother started to bring us to Nineteen Day Feasts in Belfast. For me they were small interruptions to my child’s world. I still had imagination: rich times playing on the beach, rowing our dinghy, sailing model boats on Belfast Lough, playing tennis on the front lawn and sailing with my Dad on his boat. The adult world I was now surrounded by had its own rhythm which I didn’t consciously comprehend. One day George Townshend’s son Brian came to stay with us (he was selling copies of Encyclopaedia Britannica). Hand of the Cause Dr Samandari also visited. I remember his white robe contrasting with his dark skin. Pioneers from distant lands stayed. My mother would be excited by all this, but it mainly passed over my head. I was dutifully polite but took no real interest. We started to go to summer schools. Once the school was on the other side of Belfast Lough. We sailed there in our boat, and rowed ashore with our suitcases to stay for the week. I remember Hasan Balyuzi’s children rampaging around in slightly wild ways which slightly shocked me! There were weekend schools in Bangor and Belfast. For me they were just different places to play but with similar sonic backgrounds of adult conversational drone! Another time my father sailed us across the Irish Sea to Portmadoc in Wales to attend the Colleg Harlech summer school. Life was a happy, diverse but secure adventure.

Some four years after my mother became a Bahá’í I went off to boarding school in England. I learned to live in two worlds; the world of prep school during term time and home during the holidays. They were just facets of a life in which I was an acquiescent participator. All the time our Bahá’í circle of friends was increasing. There was lovely Lizbeth Grieves, the healer; Lady Hornell, the Bahá’í pioneer; the excellent Macdonald family from Belfast, who sometimes burst into song when eating their evening meal! There was the tall Tony McCarthy and his mum, Grace Pritchard, the vegetarian, and her good friend Peggy Harrison (later to become my son Oran’s grandmother-in-law). There was big friendly Gretta and her husband Billy who swept the floor at Gallaghers tobacco factory. Later there were younger people like June Glover and Patricia Montgomery. They were all good friendly souls. Ronald Taherzadeh (Adib Taherzadeh’s son) often used to stay with us during the holidays. We spent many hours playing happily together.

One day my mother said we were going to host some Iranian Bahá’ís who were leaving Pakistan to settle in Ulster. The lovely Jamshidi family arrived and stayed with us. I remember their friendliness. Once I watched one of them say their obligatory prayer (in Arabic) and wondered about all the prostrations and hand raising. Dan Jordan was another visitor. He was a Rhodes music scholar from the USA. He stayed with us from time to time. He played the piano, dreamed musical compositions, and sometimes played incredibly exciting games with us children running around the lawn. He was such a bundle of fun. I watched him fall in love with Nancy Blair and wondered at the ‘goee coee’ nature of it all!

In the early sixties my mother asked me If I would like to leave school for a few days to attend a big Bahá’í conference in London. I had no idea what the conference was about, but being in London and not at school was attractive. I spent a week at the Royal Albert Hall and must have been one of the most unconscious attendees of the first election of the Universal House of Justice. To me, it was just another but bigger and grander occasion where a huge number of Bahá’ís from many different countries greeted each other with joyful hugs and loving cries of Allah’u’Abhá!

Later on in the sixties my mum would host all sorts of gatherings with the intention of drawing people closer to the Faith: there were music nights, discussion evenings, firesides and the like. There were many informal but intense discussions: Vietnam, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, ban the bomb, communism, humanism, anarchism, and ‘Abdul-Bahá’s 12 principles of the Bahá’í Faith were all in the mix and big debating points. Interesting Bahá’í travel teachers would pass through. There were exhibitions and poetry readings. The community was doing its best to bring people under the canopy of Bahá’í unity. For me much of it was water off my back. In my life of boarding school and holidays full of parties given by other boarding school friends, the big preoccupations were rugby and girls! The rest was a side show that was sometimes socially fun and sometimes intellectually stimulating. Unbeknown to most of us at the time, these were the last of the carefree and tranquil years when the people of Ulster could still safely and freely meet and discuss things in public. The indifference to the Bahá’í teachings of unity was soon going to reap horrible consequences for the whole community. Ulster in the later 1960’s was fast moving towards a nightmare of disunity. Social life as we knew it, in more ways than we could possibly imagine, was on the brink of changing for ever.

1968 was the hundredth anniversary of Bahá’u’lláh’s arrival in the Holy Land. A big Bahá’í conference was planned to mark this event in Palermo, Sicily. My father, who was longing for the excuse for a good sea adventure (in earlier days he had sailed to Australia and back on a four masted grain ship) offered to sail my mother to the conference. The voyage coincided with the end of my last year of school. When term finished I headed west to Cornwall to join the Winny and crew at Falmouth. It was thus that metaphorically and in reality I sailed away from my childhood and all the innocent settled life and happiness it had contained!

Some six weeks later we arrived safe and sound in Palermo. Winny found a berth in the dirty old commercial harbour of Palermo. She became the focus for many wonderful Bahá’ís who gathered on her deck. There was lots of chat, tea drinking and sharing of stories. Our guests bought with them the spirit of the conference, and the sense of an international community which fizzed with the excitement of their vision. During the conference, when visiting a famous and massively beautiful church in Monreali , a profound realisation came to me. I knew for certain that not only did I not know what the whole God thing was about but, at that point in my life, I was definitely not interested in finding out! What I did not understand was this: a nineteen year old boy had in reality taken the first conscious step on a journey to independently search for his own truth.

Back home, Northern Ireland descended into the hell of disunity. The Catholic and Protestant communities became completely and antagonistically divided. Violence erupted. The language and reality of bombs and bullets became the dominant narrative. Random acts of terrorism became the norm. The atmosphere of fear enveloped the province. Public social life shut down at 6pm…after that hardly a soul would be seen on the streets. My dad’s car was used as a car bomb (while he was at the cinema) and his van was used at different times for road blockades. His factory was burnt down. During this time my father tried to bring good rationalist common sense to this developing madness by promoting and organising interesting humanist/rationalist conferences north and south of the border. My mother was in the thick of trying to bring unity between the warring Catholic and Protestant youth tribes who lived on the estate behind our house. She organised firesides and deepenings and brought her young charges south to Bahá’í events in Dublin and Limerick. The tribes used to attend firesides and learn about tolerance and the unity of all religions. They were polite in their own way. At the end of the meeting they would offer tea and biscuits to each other. Afterwards, whichever tribe left first, routinely ambushed the other side as they made their ways home. It was a brave effort; my mum certainly waged peace. Even if it had only a marginal social effect, it was certainly hands on revolutionary activism!

But I had fledged the home by that time and so missed most of that drama.

So what did all this bring to my being and understanding?

Well, my mother skilfully infused our lives with the spirit of the Bahá’í world view, not as something alien, but as another strand of our lives. She did not push this in an insistent way, rather she used the Bahá’í understanding to underscore and bring out the best of our general Christian culture and heritage. Importantly, as I understood it, the Bahá’í teaching also chimed with my father’s humanistic values and enthusiasms. So I was given a bedrock made of two contrasting world views and a wonderful position to witness and respect lives lived as passionate idealistic endeavours. It laid a great foundation from which I could explore the world for myself. The Bahá’í spirit and logic of Bahá’í teaching must have naturally seeped into my soul and informed and shaped my world view. While at that time I had no real interest in becoming religious, in the unthreatening atmosphere which my mother created round her, I was able to come to appreciate and respect the coherence of the Bahá’í principles. I was able to see both the strengths and the shortcomings of individual Bahá’ís. I was able to recognise the warm and generous atmosphere which Bahá’ís generated when they got together. I was also able to strike up genuine friendships with lots of Bahá’ís but never feel pressurised to convert to their religion. All the early Bahá’ís that I met modelled good-hearted tolerance, patience, and a willingness to allow souls to take on their own spiritual journey. For me, one of my mother’s many achievements was the way she fostered in me a respect for her religion without creating feelings of alienation which can come from the unspoken critical judgment of parents about the ways their children are living.

Some three years and many experiences later I was given the grace to discover for myself the wondrous wisdom and truths contained in the Bahá’í Revelation. It was only then that I could truly appreciate and give thanks for the many graces that enveloped my early upbringing. I have come to understand that even if it was received unconsciously, my mother gave me a wonderfully authentic grounding in a tradition which, as it was for her, was to become one of the central concerns and passions of my life.

Now praise be to goodness for all of that!

____________________

Garry Villiers-Stuart

Burnlaw, December 2011

[1] For more information about Jane Villiers-Stuart’s path to the Bahá’í Faith, you are invited to view this YouTube video.

[2] Garry passed away on 29 July 2022

what a wonderful story, really looking forward to the next instalment

Fantastic Gary, a privilege to hear about your early life. Can’t wait for the next instalment!

I loved your story so far….very vivid pictures ….met you once…probably more…you told me you sing to your cows. That made an impression on me. Can see how your culturally rich childhood allowed you to have the freedom of spirit to do that.

Thanks Liz… am still singing to the beasts…. and you should taste the beef…ummmm!

Garry

Dear Garry,

This is such an interesting and wonderful account of your growing up years in Loughside! It brings back vivid memories of visits to your home in the 1960s, the lively discussions at meal times, the firesides that Jane organized in the community and teaching excursions in and around Belfast. And I remember your Nana who was forever kept busy cooking, cleaning and housekeeping for the family and visitors. There was always so much activity and never a dull moment in the Villiers-Stuart home! And of course who can forget Winny, anchored close to the beach in front of the house, the family boat that you are still using to sail on the high seas these days.

I am awestruck by this statement you made “The destiny of our family changed for ever”. Jane set such a fine example of the intrepid Baha’i teacher who taught with so much enthusiasm and most of all love for everyone she met without any prejudice.

Jane left behind a rich legacy, a legendary figure in the annals of the Faith in Ireland, and her outstanding services will not be forgotten in the community.

What a precious tribute you have written of your parents, thank you so much for these vivid glimpses of those early years, a special time in history for all of us to cherish in our hearts.

Thanks Ho-San… it was indeed an amazing time… and am very glad that you were there to be touched by it. But who then could have envisaged that a generation later and by an extraordinary twist of fate your beautiful daughter should then touch the lives of my children…. now there’s an intergenerational weave of magic!

Love and peace

Garry

I shared your story with Mei-Ling the other day, and she said, afterwards, how much she enjoyed it and that you had written it so well with a distinct style. She had enjoyed her experience at Burnlaw and still remembers it with warmth and affection, especially its village appeal for it reminded her of her growing up years in PNG.

Mystic connections and magic, it is all written in the wind, thanks Garry, for the privilege of your friendship.

Such a wonderful read dear Garry, a history lesson as well. When I worked at Rutland Gate in the 70s your amazing mother would drop in and a whirlwind would ensue 🙂

I hope the next instalment will follow fairly quickly…

Dear Garry,

I love reading the stories on the UK Bahá’í Histories site but yours resonated with me more than the others because your family (particularly your mother) have played such an important part in my family’s life. So many memories of visits to Loughside: the swing, the enormous greenhouse (with a jungle inside!!) a full delicious Irish breakfast which was served through a hatch (which I thought was SO cool!!!) the sea and the boats, all the nooks and crannies where we could play hide and seek, a sort of sleeping bag which was like a space suit and where Katherine used to sleep at the entrance on a couch when there were a lot of overnight visitors. I have very clear memories of 1957 even though I was only 4 years old when Ronald and I were brought up to the north of Ireland so that all the parents could go to London for Shoghi Effendi’s funeral. Nana looked after us all.

Your mother was a very loving person and my father told me after her passing of many acts of generosity and kindness that she showed towards others and that she did not want others to know about.

You have a lovely way of writing Garry, and I really look forward to Part 2!!!

Much love

Vida Stendardo (née Taherzadeh)

Thanks Vida.. Yes, Loughside and all that it contained, people and places, was such a magical world so full of innocence, intrigue and a wonderful chaos of people passing through, all of which was held together by a lovely good hearted easygoing humour and acceptance. What a grace!

Where are you now? come and visit Burnlaw… it’s got a whole different catagory of wonderful magic!

Lovely to hear from you! I have been living in Switzerland for the last 30 years. I married a wonderful Italian Baha’i and we have two sons. Don’t get to travel very much. However if ever you are in this area of the world it would be lovely to see you again! Was in touch with Katherine before her passing. Such a wonderful exchange with her. I have lost touch with Virginia and Sally. Are they also living in England? When is Part 2 of your story coming out? Much love Vida

Very good to hear from you Vida.. Ginny is alive and well and lives near Cambridge, Sally similarly so and lives near Belfast.. My brother in law is married to a Burness lady and lives in Burn! is that anywhere near you? The Winny is currenty in La Coruna waiting for a new mast!..so much adventure

See you in Switzerland maybe!?

lots of love

Garry

Well done,Garry! So interesting. Looking forward to part.

2

Hi Garry, How wonderful for me to hear about your family and early life. I can’t wait to hear more. I guess we two last met in 1972 or ’73 together in Greystones with Juan Lugo. Remember him? Amazing to read all this now. Fondest love to you. Mary.

Greetings and thanks Mary… Greystones, No 6 Willow Terrace!… Now there was another magical place that witnessed wonder.

Some years back I met Juan in a dream… and we whirled round and round dancing on top of a Colombian mountain!

Had an amazing adventure last summer. You can follow it on http://www.winnyvoyage.com

See you soon I hope

keep well

Garry

A great insight into growing up in a home with different points of view – a well rounded upbringing. Awaiting the 2nd part Garry of a fantastic story and family. Much bliss and great voyages yet to come.

Thanks Peter and bliss to you too!

Garry

Thank you Garry for this fascinating and insightful account of those distant days in Northern Ireland. Your family were so interwoven with my own and those same extraordinary people – your Mum and Dad of course, your dear sisters and Mary.

The domestic chaos of Loughside with that great range pulsing out heat in the back kitchen; being able to dive into the Lough just feet from your garden wall; playing tennis on the front lawn with its odd bumps which frustratingly sent the ball in random directions! The dedication of your mother to the Faith was absolute; but for once I understood from your story how that remarkable divergence of belief between your parents actually played out. Your Dad allowed Tony and me to sail on the ‘Winifred’ (Winny) on occasion, and I remember we sailed once across the Lough to a weekend school in Bangor. People cried out from the quay “Where have you come from?” We answered “Greenisland”, but then heard someone say “Do you know they have just sailed from Greenland!”

Trips to Dublin in your Mum’s famous van, with her frightening habit of chatting away with her head turned towards the passengers, and then crying “Oh Goodness!” as we nearly hit another vehicle! Baha’u’llah protected us all!

I noted the bit about the Macdonald family breaking into song at the meal table. Yes my Dad sustained a positive medley of songs – from Irish Rebel to Paul Robeson!

Anyway many thanks for stirring such deep and loving memories of those unique days in Ulster with its equally unique politics and perspectives, and a Bahá’i life of great richness.

Thanks Ian… I also remember that memorable Harlech Summer School in which (initiated by you and your sense of drama) we dressed up as medieval knights and had endless fun battling with swords on the terraces and parapets of Colleg Harlech.

Such simple and totally engrossing innocent fun!

Then there were those mid sixties years with the buzziing Baha’i center on that top floor in Linen Hall Street just above the CND office.

There was such an optimistic sense of the possible…. all dashed by later events

Dear Garry

it was lovely to relive those unforgettable Loughside days and it is important that you, Sally and Virginia write down the stories about your Mum as there is a risk that many a hadith will be created as the years go by.

There are so many memories that I would love to share but maybe I will put them in my own story when I can eventually get kick started to write it. I remember helping your Mum to vacuum the house and clean the loft before big meetings and then being sent off to have a bath before the meeting began because that would relax me. I remember the last minute baking of wheaten bread in the chaotic kitchen and the special gingerbread that your Dad used to bake on the Winnie.

Pussy was an important, rather promiscuous member of the family that you omitted to mention. She lived in the barn and produced many litters of kittens from various fathers. Our much loved ginger McGinty was one of them.

I went out on the Winnie several times including during the Palermo Conference when you were very much the young man about town. I still have a photograph of a group of us who went out to dinner in Palermo. Yes, Monreal Cathedral is incredible and I can understand why you were affected by it.

So many wonderful memories but perhaps the one that I cherish the most was the last time that I saw your Dad the day before he passed away. He was in hospital and very frail but ever courteous and loving. I can still picture his shining eyes and sweet smile as he raised his frail arm to wave goodbye to me.

Much love, Hazel

Greeting love and thanks Hazel…. yes Loughside was never dull, such a succession of mini dramas! It all contributed to the incredible richness of place and atmosphere…let me encourage you to start immediately with your own recollections.

lots of love and happiness to you

Garry

Dear Gary,

Wow, what a wonderful childhood, so exciting!!! Full of spirituality and also of international interactions. How did you become so musical – you haven’t mentioned music at all? This was such a joy to read, thank you for sharing it Garry, very much looking forward to part 2.

Love,

Simin

Thanks Simin – yes is was all nearly fairytale… music, such an important key to my unfolding destiny (and to the transcendent) came later… If there is appetite, that story will also be told.

Big happiness to you

Garry

Dear Garry,

Thank you for your lovely life history part 1. As luke warm Christians, the Irish troubles which we found when we moved to Dublin in 1967 led us to believe that the religion we knew was failing.

The wisdom in your father being a Humanist is that, ardent Humanists as Maureen and I then were, we might meet your lovely mother at a humanist conference in the North, about 1968. Your mother invited us along to a Baha’i Summer School in Dublin, where they were very kind to us and our young boys Timothy and Jonathan. For lunch I remember being sat between Charles McDonald and Keith Munro. It was impossible to resist the love and charms of the Dublin community, with John and Val Morley, the O’Briens, Zebbie Whitehead and many more.

Love Michael and Maureen

I didn’t get to meet your wonderful family until the late 70’s. Your Mum (and her rusty Ford Transit) were very influential in my becoming a Baha’i and my Baha’i life ever since. I very much enjoyed reading about the earlier history.

An important historical document in more ways than one; infused with Garry’s inimitable charm and eloquence; moving and beautifully written.

Pingback: Garry Villiers-Stuart – Part 2 “Unconsciously becoming conscious” | UK Baha'i Histories

When i first came upto Alston Moor in the mid 70’s i heard people speak of Garry & Rosie the Baha’i’s nr Whitfield……… I have never met you or Rosie but i had a feeling it was you both t’other night at the Whitfield school gathering benefit. Look forward to the next instalment 😉

Hi Jan, yes we were there.. and what a good event. Next instalment is up ‘unconsciously becoming conscious’ hope you enjoy.

lets meet! Garry

Hello! I never met you in person but I did meet your dear mom and do recall meeting your sisters at the Irish Baha’i Summer School at Waterford in 1976. I did meet you by phone a few decades later and I cannot recall where. I was traveling through the British Isles and picked up the phone and called the Baha’i number listed in the phone book. You answered the phone and we must have been on for a hour at least! You were just as eloquent and open and friendly as your stories portray you. Best wishes to you!

– Victoria de Leon

Pingback: Lorna Silverstein | UK Baha'i Histories

Lovely to see Winnie sailing again. We looked after her for a year in Malta and met you and Ginny. Best wishes, Harvey and Roberta Fudge.

Big thanks Harvey, you must have done a grand job…. Since then Winny has sailed me to many bliss places inner and outer

Hi Gary, I met your sister Sally Liya in Zaire in the 1970’s and later at IITA in Nigeria.

Hi, Garry, this is a very lovely and inspiring account. Reading your account has made me respect your sister Sally more than I did when we shared the same flat in Ibadan when she was studying for her Ph.D. Unfortunately, we’ve lost all contact with her. My wife joins me in sending her love and greetings! I can be reached at [contact details given]

Warmly,

Enoch Tanyi

Dear Garry i’m Désiré Liya Sally’s step son leaving at Kinshasa, how can i be in contact with you and Virginia Villiers Stuart , please help me to be in contact with you..