All what Jazz?

I was born in the town of Keith in Banffshire in 1960, but grew up in India Street, (two blocks away from the present Bahá’í Centre) in the city of Edinburgh, which I still consider home. My Scottish father and English mother, both born in the 1930s into families of devout churchgoers, had, like many of their generation, turned aside from the suffocating orthodoxies of their youth well before my birth. Consequently, I was never christened, but left to draw my own conclusions about religious and spiritual issues, which indeed interested me very little. Nor did the study of physics, for that matter, as I discovered when I enrolled as a student of “Natural Philosophy” at the University of Edinburgh in 1978. Clearly unprepared for adult life, there may have been trouble ahead, but there was also music, and laughter, and love and romance…

…well, music anyway. And the music, the dancing, loving, laughing, unspeakably romantic music which captured the heart of my youth, was jazz.

Some people stand out, even amongst the hoards of bouncy, buzzing, boozing newly-freed aspiring grown-ups who populated University Freshers Week. While greedily soaking up the bohemian ambience of student night life, I couldn’t but help noticing one figure in particular, again and again – in the refectory in Potterrow, at the Freshers Week concerts, on the stairs of the student union. It wasn’t that he stood out because of any special aura or charisma. It was simply that he was the most ridiculously dressed person I’d ever seen. One day it was a shining silver suit with bootlace tie, spiky brylcreemed hair and winklepicker shoes. Another it was chest-high pinstripe baggy trousers and black fishtail coat. A veritable plaything for the ignorant. I was pretty ignorant, and seriously impressed.

But I was on a mission. A postcard in Teviot Row won me some contact from fellow jazz aficionados. This culminated in a meet in Alison House (the music department) with a trombonist, a pianist, a tenor banjo player, a trumpet player and a very hairy Irish pianist called Pat O’Connell (who turned out indeed to be a direct descendant of The Great Emancipator, Daniel O’Connell himself). With fame on our side, not to mention some sight-readers, things were going well. All we needed was a drummer. Then, just as we were about to disperse, the door opened, and to my delight, who should slide in shyly but Mr Bespectacled Winkelpicker himself, replete with tailcoat and drumsticks. Thus was born “The Rhythm Method” – undoubtedly Edinburgh’s worst-named Jazz Band, though we had our moments, one of which was drummer Richard Fusco’s attempt at tap-dancing to the strains of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” on the second floor of “Le Tour Eiffel” in the summer of 1979…

Mortal Sovereignty

It wasn’t the only memorable event of 1979.

The rather smart new housing development (St John’s Hill) at the foot of the Pleasance was then, like much of Edinburgh’s south side in the late 1970s, a rather dreary piece of scrub land, full of red clay, broken stones and sickly-looking couch grass. Just what took me there, in the company of jazz drummer and fellow science student Richard Fusco, I am at a loss to remember. It wasn’t on the way to anywhere worth going, and, yards away from the old Salvation Army men’s hostel, wasn’t a particularly salubrious haunt. What I remember vividly, and am unlikely ever to forget, was that it was the place where I first encountered the written Word of Bahá’u’lláh. The text was in a little black Gideons New Testament-like book resembling the freebies we got at school, laid out on florally illuminated pages. This was today’s gambit on Richard’s part, apparently, to demonstrate (in the light of the previous evening’s heated discussion) that playing the clarinet better than Benny Goodman wasn’t a sensible aspiration to which a failing physics student (me) should dedicate the rest of his life. I, full of dreams, begged to differ, but nevertheless politely perused the strange poem-thing thrust before me.

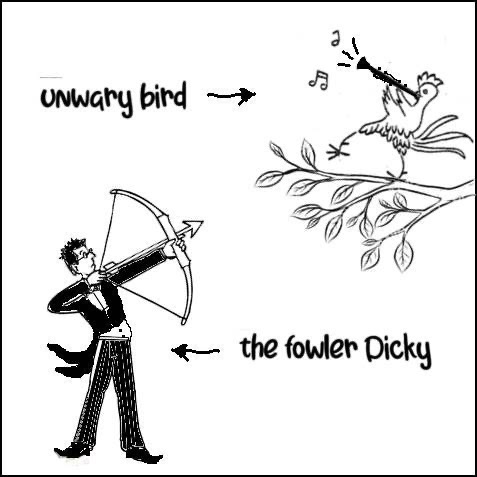

“O CHILDREN OF NEGLIGENCE!” it read,“Set not your affections on mortal sovereignty and rejoice not therein. Ye are even as the unwary bird that with full confidence warbleth upon the bough; till of a sudden the fowler Death throws it upon the dust, and the melody, the form and the colour are gone, leaving not a trace. Wherefore take heed, O bondslaves of desire!”

This child of negligence looked at his friend, incredulously. “You what?”, I asked.

Richard extended his hand palm upwards with the satisfied flourish of a triumphant magician who had pulled not just a rabbit but the entire meaning of life out of an empty top hat. The simple fact that he had presented this unwary bird with a stern admonishment from none less than the Supreme Manifestation of God for this Day, was to him clearly conclusive, and I would ergo have no choice but to concede the argument.

The bondslave of desire wasn’t convinced. “Come again?” I repeated.

It wasn’t so much that I disagreed with the poem (ok, scripture-thingy) than that I hadn’t the foggiest idea what it meant. I’d never heard of Negligence, never mind his kids, and was vaguely wondering what sovereignty, a fowler, and a bondslave were. And what was with the flowery patterns…?

Richard patiently explained that a fowler was someone who killed birds, and that the verse meant that we were all going to die anyway, so what was the point? And besides, I wasn’t that good a clarinettist anyway.

I had to give him that.

Not all journeys begin with a fanfare. I faced many milestones and crossroads, not to mention a few pitfalls, in those first steps on the long pilgrimage which rolls out life’s carpet for those of us who elect to bear God’s name. But I remain convinced (as any devout educated Muslim can explain) that the needle of direct encounter with the revealed Word can weave mysterious and powerful threads through the heart and soul of the reader. Forty years on, I marvel at the courage of a young Bahá’í who must have realised he was risking not only potential ridicule, but perhaps the cooling of a valued friendship, by sharing a Hidden Word with an avowed atheist. But he could see its relevance (even if I couldn’t) and took the risk. Perhaps prayer won, over common sense, and my gratitude to my friend for this courageous act will go with me to my grave.

I liked Richard but was uneasy about his rather strange faith. I was consciously suspicious of religion and cults, but there were other quiet voices lurking in my soul, and behind the outer bluster of my pompous and assertive temperament, I was discovering what must have been a sincere thirst for truth. The conversations became more frequent, and more meaningful. I met more Bahá’ís. Some were Persian. They had great parties – the Bahá’ís called them holy days and feasts. The prayers were like heavenly music. The food was divine. The girls were beautiful.

Then someone lent me Gloria Faizi’s little blue book The Bahá’í Faith and I hit my first devastating pitfall, a deep pothole in my road to acceptance of the New Revelation.

“I won’t be becoming a Bahá’í!” I announced to Richard at the gig that night.

He kept disconcertingly calm. “Fair enough. Why not?”

I explained that I couldn’t possibly subscribe to a lifestyle that precluded sex before marriage.

He mused for a moment “Indeed,” he responded, “And why’s that a problem?”

I hesitated. It wasn’t the response I’d expected. How did I put it into words? It seemed quite obvious to me, despite the fact I’d never actually considered the question before.

He went on, “Now, it might be a problem for Errol Flynn, or Paul Newman, or even Bill over there.” Handsome, dark-haired Bill did seem to have to fight the girls off now and again. “But for the likes of me and you – what’s our chances of finding a female, any time soon, desperate or deranged enough to crawl into bed with either of us?”

I looked around. Certainly I didn’t see any such desperate or deranged females in the pub that evening. In fact, come to think of it, I hadn’t encountered any such desperate or deranged females anywhere in the last year. Or two. Or three. His argument was puerile, of course. But oddly convincing…

I climbed out of the pothole, dusted down my slightly bruised virginal ego and soldiered on along the road. After all, maybe, if I couldn’t find someone to sleep with me, I could find someone who’d agree to marry me…

There were other twists in the winding road to declaration. I didn’t believe in God for one thing. That seemed to present a barrier to my accepting Bahá’u’lláh in the minds of some of the friends who talked with me, but it didn’t really bother me. I suppose I wasn’t convinced that what other “religious” people believed in was actually God. Privately, I thought Bahá’u’lláh’s Writings seemed to back me up. It all seemed to boil down to semantics. I suppose I was learning what “faith” meant.

Alcohol was less of a problem. Becoming a Bahá’í was a rather welcome excuse to give it a miss, save money and enjoy parties for longer. Politics was kind of boring, anyway. Fasting presented more of a challenge, but at nineteen years old seemed rather fun.

I sometimes think becoming a Bahá’í is a bit like falling in love. The underlying motivation is there, and grows as we move closer along the road. But we have our questions, our defences, which keep us from throwing ourselves on the waves. We discard them gradually, one by one. Then we’re carried away by the flood. Just as well I was never a particularly learned grammarian.

Still a student, I eventually declared my faith in the summer of 1980, after being somewhat piqued that I wasn’t allowed to go to a meeting about the Covenant just because I wasn’t an enrolled believer. The pilgrimage proper had begun, and it’s still going on, nearly forty years later.

And I still can’t play the clarinet better than Benny Goodman.

Escapades

It was a good time to be a new Bahá’í in Scotland. We had a centre in North Fort Street in Edinburgh, a vibrant University Bahá’í Society, Riḍvan Moqbel’s phenomenal fortnightly firesides in Glasgow, and a richly-diverse growing community of Scottish believers. As well as the distinguished Persian families and the many devoted English pioneers, there were Grants, MacLeods, Mackays, Ballentynes, Donalds, Hulmes, Carnies, Murrays, MacKenzies, Duncans, Reids, Leonards, Hills and Sinclairs from across the country. A huge inspiration for an east coast lad like myself was the warmth and fellowship of the west-coast Hibernian-named pioneers littering the country, afire with the spirit of service – Keenans, McCaffertys, Boyles, O’Rourkes, Nisbets, O’Brians, Dochertys, Morrisseys and others. It’s hard to conceive how much I learned, not only about the history and principles of the Cause of God, but about my own country and culture, the meaning of service, sincere dedication and selfless love, from what became to me a warm and welcoming big new family. Profound and intriguing stories abounded, songs and music enlivened gatherings. Light and untrammelled as the wind, we had huge fun dancing around the country, living in castles, playing with boats, digging graves, setting up new LSAs and groups, opening new territories, holding conferences and weekend schools, visiting isolated believers, and of course doing what we could to serve, or, as we called it in those days, to teach the Cause.

Weaving through the swirling party of service, though, was a theme that held a particular significance, and indeed a powerful fascination for the young Scottish community of the 70s and 80s. I first became aware of it via a peculiar and intriguing flyer pinned up on the noticeboard of the Edinburgh Centre. It was simply headed “ISLANDS”. I couldn’t see the relevance. Never mind what it was going to mean for my own unfolding destiny…

Medical student John Parris explained it to me with unbridled enthusiasm. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had named three specific territories within the British Isles in the Tablet of the Divine Plan revealed on April 11, 1916; The Hebrides Islands, the Shetland Islands and the Orkney Islands; all of them, of course in Scotland. Consequently, the Guardian had designated these islands as key territories in the Ten-Year World Crusade. The islands remained a key teaching focus not only for the friends serving in Scotland but for the entire UK community. Shortly after I became aware of the notion that islands hold a special significance in the unfolding destiny of the British Bahá’í community, the NSA began organising Islands Conferences. The first of these, in Inverness in 1981, spawned a number of travel teaching trips. Richard and I set off westward immediately to hoist the Standard of Yá Bahá’u’l Abhá above the spiritually pregnant Gaelic-speaking Isle of Benbecula. We had bus tickets. We had a ferry timetable. We knew there was a Bahá’í living there called Peter Bird. Entry by troops had virtually begun and victory was all but assured! What could possibly go wrong?

All went to plan. Problem was, the plan left a bit to be desired. My initial encounter with islands was somewhat chilly, to say the least. They say some islands, though bleak, are magical and beautiful. This one was just bleak, especially at 5.00am. Especially when the first bus from the deserted pier was at 8.00am and you hadn’t had the wit to ask for a lift. Especially when there was no shelter to wait in. Especially when it started to chuck it down in buckets and neither of you had thought to bring a raincoat. Five hundred “Remover of Difficulties” didn’t stop the rain, but it did get us to Peter’s Caravan, Peter’s empty caravan.

A helpful neighbour came out and explained Peter was away on holiday, but she took us in, dried our drenched clothes, parked us by the peat fire and fed us a hearty breakfast. Something of the magic of remote island life began to warm my soul…

Opening an island on Loch Ness – with John Parris

Seeds

A year later, I awoke from a doze in the fore passenger cabin of the ferry Orcadia, which served the North Isles of Orkney in the early 1980s. The boat was pulling in to a pier, but in those pre-tourism days no-one had thought to put a sign up to inform strangers which island it was. I turned to a fellow passenger, waiting to disembark. “Excuse me, is this Eday?”

He looked at me quizzically. “Oh yaas. Are thou a towrist?”

“Er, sort of..” I replied, fumbling in my jacket pocket. I pulled out an old photo my father had given me. “This is where my grandfather was from. Robert Miller.” (I pointed) “From Stenaquoy farm.”

He took the photo and studied it. A soft smile played on his lips and he handed it back to me. “That wis me uncle”, he said quietly.

Word spread across the seven-mile-long isle like a forest fire. I was the prodigal returned. Old Billy Gray, booked to drive me to the youth hostel, insisted on taking me to his house for a cup of tea. “Daisy!” he announced to his wife as he led me in to their tiny ‘but and ben, a two-roomed cottage, “This young man is a grandson o’ Robbie Miller o’ Stenaquoy!”

I lasted one night in the youth hostel before being whipped away to stay with John-Robert, my father’s cousin, and his wife Reta, to experience the full onset of old Orkney hospitality. I was driven round the neighbours, introduced to long-lost relatives, fed like a prince and taken out to the creels. Bobbing about in a fresh breeze in a tiny boat, lobsters at my feet and seals peeping above the surface of a breathtakingly blue summer-sea, I thought I’d died and woken in the Abhá Kingdom.

Saturday night, stretched out before a cosy range after a meal of home-grown mutton and clapshot, my hostess Reta asked me if I wanted to join them in the morning to go to church. Here was my chance! Today I still wince at my response:

“Actually,” I blurted out, “I don’t go to church. I’m a Bahá’í!”

Reta and John looked at me curiously. Instantly, I realised my mistake. Had I made myself suddenly unwelcome? Had I caused offence? Did I blaspheme? Were the lights about to dim suddenly and a hurling fury see me cast out to the elements like Tam’o’Shanter driven from Alloway’s auld Kirk by Clootie and his witches?

No such reaction. Instead, Reta got up deliberately and walked over to the dresser in the corner. She opened a drawer and took out a silk handkerchief, drawing it through her hands she passed it to me.

“Mrs Faizi gave me this.” she explained calmly. “As a thank-you for our hospitality.” “What? Gloria Faizi? The Bahá’í?”I asked, rather incredulously. She chuckled. “Yaas, that’s right! The Bahá’í Mrs Faizi. She was a very fine buddy, we thought.”

I found out subsequently that Gloria Faizi had made a point of visiting the small islands in Orkney when she went there travel teaching. I’m sure she’d have been tickled if she’d known how warmly she had been remembered.

John sat pondering for a minute.

“There was a Dr Miller used to come to do locums from Caithness” he recalled. “He was a Bahá’í. When the Minister was away he used to take the lesson in the Kirk.”

It was true. Dr Miller (no relation!) was a known early believer in Scotland who practised in Wick. The thought of him mounting the pulpit in the Eday Kirk and delivering the sermon to a staunch Presbyterian congregation is intriguing. He must have taken the opportunity, however discreetly, to share the teachings and principles of the Blessed Beauty in those lessons, to attentive and receptive ears.

Seeds. We sow them and nurture them, or we cast them to the wind, hoping some will take root, and some will. Perhaps all of them will, in the end. One of our recent new believers in Orkney became a Bahá’í decades after a caring visitor who was a Bahá’í showed her a little kindness. At the same time another new believer who had cared for Irene Bennett and Betty Shepherd was so deeply impressed by their quiet and assured faith that she investigated the Cause herself and has now become a Bahá’í. We yearn, naturally, to see the fruits of our efforts. But more often than not in these times it seems we are disappointed. We need in the end to trust in God, I suppose, and rest assured that no sincere efforts will be wasted.

Blessed is the spot, and the house, and the place, and the city, and the heart, and the mountain, and the refuge, and the cave, and the valley, and the land, and the sea, and the island, and the meadow where mention of God hath been made, and His praise glorified.

I got a job in Orkney the following year. Then (as now) the air, the waves and the soil here were heavy with seeds.

Friends gathered at the Orkney Temple Land to celebrate the Bicentenary of the Birth of the Báb, October 2019

Wisdom

Number 7, Haparsim Street, Haifa. 1983. I was droning on rather incoherently, trying to ask a question about international pioneering. She interrupted me. “You stay in Orkney!” she said.

I hesitated, not sure what to say. She went on, “Everyone thinks it’s all about international pioneering. But the home front – Shoghi Effendi used to call it the home front – the home front is just as important. You don’t have to go travelling around the world to serve Bahá’u’lláh. There’s work to be done where you live, too. Important work. You stay in Orkney.”

Amatu’l Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum wasn’t looking for a conversation. Hand of the Cause and our last link with the Holy Family, she was clearly well past the phase (if she ever went through it) of offering platitudes and sugary talk. She was also well-versed in dealing with silly questions (like mine – whatever it was) from the friends in Q. & A. gatherings like this. I wasn’t the only pilgrim to win a sharp and pertinent response. “Oh please don’t use that term!” she interrupted as someone was talking about “declarations” in their community, “Why do Bahá’ís keep talking about “declarants” and “declarations”? Such a horrible word! Can’t they just call people “new Bahá’ís” or “newly-enrolled believers” or something like that?” Now I avoid the term “declaration” and declarant” as best I can.

We loved Khánum’s bluntness in Scotland. She was proud of her Scottish roots and we in turn liked to see in her no-nonsense down-to-earth discourse an aspect of her Scottish inheritance. Sean O’Rourke (who lived on the same Glasgow street as Benny Lynch, the legendary featherweight boxing champion, a generation later) used to describe how his dad and his mates would have investigated the Faith had the occasion arisen. They would have sat by the bar in the pub, pints in hands, exchanging pugnacious verbal blows, punctuated with the thumping of fists on tables, on the pros and cons of a universal language, the equality of women, the need for world government and the essential brotherhood of man (whilst of course respectfully avoiding the taboo subjects of politics and religion) until all was duly thrashed out and the case was won, or closing time forced an adjournment.

Khánum would have readily held sway in those dialogues. I once watched her, in Edinburgh, utterly demolish a Persian believer who was challenging, in Farsi, the decision to inter the remains of Shoghi Effendi in London. She was patient, and cutting, and made no bones about the pain the oft repeated question caused her. If I had been that believer I’d have prayed for the ground to open up and swallow me.

She loved to visit Scotland, and like seven other Hands of the Cause, had, throughout the preceding years, visited the islands listed in the Divine Plan. Jo and Barry Constantine were living in an old wooden house near Dingieshowe at the time of her first visit. New baby in tow, Jo was just preparing the evening meal as Barry returned from an LSA meeting. If anyone can cap a Scot for direct talk, it’s a Yorkshireman. “Better mek more of that soup,” he suggested. “Why?”, Jo enquired. “Shoghi Effendi’s missus is coming over for dinner,” he replied, without looking up from his bowl.

Poor Jo! And come Khánum did. She doubtless enjoyed the warm Yorkshire hospitality. She seated herself in a corner and took the baby. “What’s his name?” she asked. “David.” was the answer. “Oh good!” said Khanum, “I’m so glad you’ve not given him one of those silly Persian names!” This lady understood that a spade, as they say in the Dales, is a spade.

“You stay in Orkney”. Personally I only ever had that one exchange of words with Rúhíyyih Khanum, in Haifa in 1983. I did leave Orkney in 1988, but only for a time as it turned out, and I consequently missed the chance to meet with her in the islands. I found myself back here though, at the turn of the century, for better or for worse. I had left Orkney for sensible reasons, but it didn’t feel right being away. Khanum’s advice still echoes, and my night-watchman continues to follow me…

When the swords flash…

The Fortress

Since becoming a Bahá’í, I’ve lived up and down Scotland’s east coast: the Borders, Lothians, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Banff and Buchan, Easter Ross, Shetland, and of course, Orkney. I’ve drawn huge inspiration from the (Hebrides) Islands of the West coast from visits to Lewis, Harris, the Uists and Benbecula, Mull and Skye. The many pioneers who served there, and who welcomed and taught me so much, have left a rich tapestry of memories. I’ve served over the decades on six Spiritual Assemblies in Scotland, and lived in groups and as an isolated believer. In Orkney and Shetland I’ve lived on five different islands. While living, in 1985, on the island of Eday in Orkney, on a trip to Aberdeen I met Lorraine Carroll, an extraordinary, inspiring girl from Glasgow who discovered the Faith living on another small island (Whalsay) in Shetland. Therein’s another story – but hers to tell. Three years later we were married – embarking together on the astonishing voyage that marks the passage of family life.

Yet I wonder if our greatest achievements are rather like our most profound stories – outwardly unremarkable, little celebrated and seldom told. A string of gentle, personal moments, which we can cherish, but not often or easily share. Like the sheer beauty of my first-born’s blinking eyes or the softness of my wife’s prayers, or the moment my children ran into the kitchen excitedly shouting “The Bahá’í Faith is on the Simpsons!!” To be exact, I think Bart Simpson’s exact words, to encourage the neighbouring Flanders kids in the “Christian Convert” computer game they were playing, were “Quick – get the Goody-Goody Bahá’í!” Trivial perhaps, but it meant a lot to me that it meant a lot to my kids, and it still does. Maybe it was some kind of whimsical, daft affirmation that Lorraine and I had managed somehow to bring forth ones “who will make mention of Me amid My servants.”

Raising our families, pursuing our professions, building lasting friendships, finding manageable and sustainable ways to serve Bahá’u’lláh, are often less- than memorable experiences, blending into the stuff of mundane, day to day routines and the repetitive patterns of life, but isn’t that the real tale? In these “far flung”, “inhospitable” islands there have been warm joys and bleak sorrows, laughter and anger, loneliness and companionship, the most precious of which has been that of my long-suffering spouse, Lorraine…(“Through all the worlds of God…” I tease. “Dear Lord, don’t remind me…” she murmurs…)

In my sixtieth year, forty years on from those first promptings to “arise and serve” the Cause of God in my native land, perhaps I’m not alone amongst Bahá’u’lláh’s footsoldiers on the home front in asking myself “What have I done? Why haven’t I done more?” At such times I take comfort in the words of the Knight of Bahá’u’lláh to Orkney, Charles Dunning:

“I did at least go and I can assure whoever goes will have rebuffs. But remember this, no one can remove the footprints you made, or the echo of your voice, or the smiles you gave and those you got in return, and as you go around in your travels, you will see beauty spots, all belonging to God.”

_________________

Steve Miller

Orkney, December 2019

Hey Steve! I feel sure I met you several times in Edinburgh when I was working there at the Regional Council in younger days. That was back in 1979-1980. I still recall a few Baha’i youth in that city who came together to play music , and one who was, as I thought, a great clarinettist! Many names are now a fog, but I think he was what people these days call ” a friend of the Faith”… I still recall the melody of the mellow sound of the clarinet and his friendly, unassuming enthusiasm. Am fairly sure it was your good self!

What a deliciously written story. I met Ruhiyyih Khanum on Orkney when she paid a quick visit, and can just picture her from your description xxx

What a riveting and remarkable story. I shall never forget Steve and Lorraine…

Thank you Steve inspiring footsteps you have travelled on your journey. Loved you story 🙂 Also your love for the islands of your ancestors.

Islands yes – Pathead maybe?

Such a beautiful story, the writing so exquisitely crafted, even the pictures lovingly selected to complement the superb writing.

I think we are related too my Great Grandfather was Robbie Miller of Stenaquoy. My Granny was his daughter Jean Miller