My earliest childhood memories are of my dear father chanting Bahá’í prayers. Many years before this, my father and his brother Uncle Jacoub secretly attended weekly Bahá’í children’s classes. Coming from an orthodox Jewish family in Kashan, this needed to be kept quiet from other relatives. At the time there was a lot of excitement in the Jewish community about the Bahá’í Faith. It is Uncle Jacoub’s story of spiritual awakening that shaped my spiritual conviction as a child.

Born to a poor hard-working family, Jacoub found employment in a Bahá’í home. Attracted to the teachings, one evening he accepted to eat their non-kosher food, expecting severe retribution. During the night he tossed and turned, beset with physical and spiritual discomfort. He dreamed of a Figure and heard a voice, telling him, three times, “Be assured, be assured, be assured.” In the morning he asked his employer to see a picture of Bahá’u’lláh, only to be told that he should travel to Haifa, to the house of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, where it was kept. He committed to travelling there. When he arrived in Haifa some years later, Bahíyyih Khánum permitted him to enter the house. Upon seeing the picture, he saw the Figure of his dream and fainted. I loved Jacoub.

We grew up in Arak, a small town west of Kashan. Friends came to play in the large garden with many fruit trees. I learned dressmaking from my dear mother. Many family members regularly attended synagogue. My parents, Shabon Saedi and Heshmat Saedi, supported me in my spiritual quest and I remember my father chanting prayers in Hebrew. There were no printed Bahá’í books, so we relied on learned travelling Bahá’ís to bring news. Life was hard and the winters severe. My dear father would leave for market at 4am to bring a camel-load of provisions for the winter. Snow would often be a metre deep. Nothing tasted better than mother’s cherry-flavoured iced drink.

From around 7 or 8 years old – the late 1930s – I remember hearing adults talking with hatred about Bahá’ís and Jews. We moved to Tehran for my higher education where Bahá’ís had more freedom. I hoped to study medicine. After high school I did a year’s preparation for university entrance, studying Anatomy, Physiology, English & Maths. The university entrance exam was tough, eighty questions on four subjects in eighty minutes. Only 400 of the 4,000 students would pass. Sadly, women had little chance; boys took nearly all the places. Rich families wanting their sons to avoid conscription would bribe exam officials. After trying for university entrance, I spent a year teaching outside of Tehran. The winters were difficult, muddy roads, and children’s heads full of lice. Returning to Tehran I again sat the entrance exam, and again failed.

The large Tehran Bahá’í centre hosted youth meetings every two weeks, filled with joy, music and singing. Dear Mr Furutan visited in 1953 with talks encouraging the youth to pioneer during the Ten Year Crusade. With his lovely smile he told us it was time to separate and travel teach at home or abroad. By chance I met an old school friend about to travel to London to study nursing. The pay was good and the qualifications invaluable. Things started falling into place.

Divine assistance came to me in three ways. I passed an English exam enabling me to get a passport. I applied for a midwifery training post at London’s Battersea General and Bolingbrook Hospital. Miraculously, the matron had a friend in Tehran who interviewed me over Sunday tea. Then, most emotionally, with the blessings of Bahá’u’lláh my parents managed to pay for the flight to London. There were tears. A young Persian girl, travelling alone in late 1953, it was like going to the moon. Over the next twenty years, all my sisters and most of my cousins emigrated. I saw my parents only twice again. They passed away in the mid/late 1970s.

The first year of studies was very hard. I worked all day, improving my English at night. Life was very different and I missed home. Matron was rather severe. She noticed me falling asleep while reading so suggested that I walk and read. My only anchor was trusting in Bahá’u’lláh. life became easier through prayer and teaching which became the centre of my life. True faith came later, not long after hearing about the passing of the Guardian. Under the pressure of work and missing my family I had questions for God. Prayer and meditation sustained me.

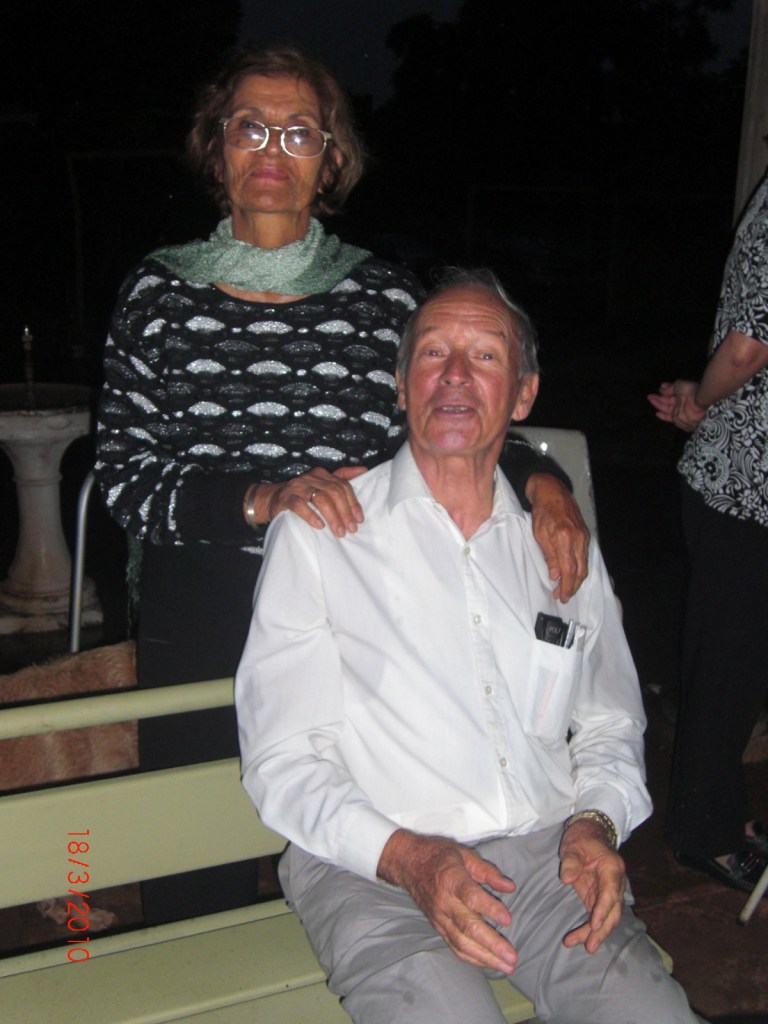

A few months before finishing the midwifery course, I took a holiday job at a nursing home near Epsom, travelling daily on Southern Railways. One morning after a night shift, when I was in a rather sleepy state, a young clean-looking chap wished me a good sleep. That same evening, at the very same Clapham Junction, then one of the busiest stations in the world, we bumped into each other again. He cheekily said, “I knew we’d meet again but didn’t know so soon.” That was the beginning of a lasting friendship. Charles and I married six months later, in March 1960. We planned a small registry office wedding followed by a Bahá’í ceremony at 27 Rutland Gate. Ahmad Djalili took photographs and guests included Betty Reed and Meherangiz Munsiff. My mother-in-law, Agnes, was very impressed with the diverse nature of the gathering.

I moved to Barnes, southwest London, to live with Charles, his mother and his sister Arlette. Working as a district nurse, I would travel by bicycle, visiting patients in their homes. My patch extended from Shepherd’s Bush to Hampton – I thought nothing of pedalling ten miles down the A3 in full uniform. It was quite a lonely time. Charles was not a Bahá’í, and there weren’t many ‘friends’ yet in the community of Richmond. But soon, an au pair settled nearby, followed by Mahmoud and Victoria Afsharian. Later, Noreen and Farhad Tehrani moved to Richmond. We became an active group, holding regular deepening classes and firesides, and invited the Mayor to a tree-planting. In 1963, we attended the First World Congress at the Royal Albert Hall. Our first son, Paul, was barely a year old so we took it all in from the balcony. Charles attended the public lectures. He listened carefully and shared his learnings with his mother and sister. In 1966 the community was blessed by a visit from Hand of the Cause, Mr Samandari. I remember someone reaching for a prayer book and he reminding us of the importance of memorising prayers.

In 1965 we decided to visit my family in Iran. We agreed to drive to Tehran and return by train. An adventure it unsurprisingly was, and for Charles a transformation. Stopping in Shiraz before driving on to Tehran we visited the Holy site, the House of the Báb. God’s kindness and mercy poured out. The custodian requested that we visit the upper chamber separately. Charles, waiting downstairs, picked up a copy of Portals to Freedom, his first Bahá’í book. Engrossed, he prayed that I would not come down, while I, upstairs, prayed that he would pick up the book. The Spirit of the Faith came to him. He cried in that room of the beloved Báb. Back in London, later that year, after attending a summer school in Italy, Charles declared in the home of Earl and Audrey Cameron.

Hand of the Cause Mr Furutan was travelling across Persia while we were there. So we made a travel plan to follow him. He soon noticed, his beautiful smile reassured us. Most memorable was an evening meeting in Shiraz attended by many hundreds. That night a young man chanted, his voice heavenly, unforgettable. Nearly twenty years later, at summer school near Bulawayo, I heard that voice again. He confirmed that yes, it was him, and he was now pioneering in Zambia. But sadly Sohráb Rouhani has since taken his heavenly voice with him to the Abhá Kingdom.

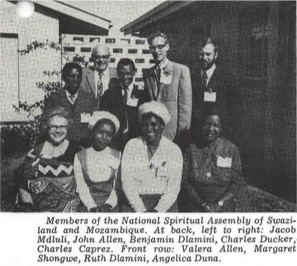

We became an active Richmond community. One evening in 1967 the doorbell rang. A tall American had been directed to our house to attend the Nineteen-Day Feast. Dale Allen was en route back to his home in Swaziland. On fire with the love of Bahá’u’lláh, he instilled in us the desire to pioneer. Coincidentally, the National Assembly had a goal of sending two pioneers to Swaziland. When we met with the Pioneering Committee, Adib Taherzadeh asked if we knew where Swaziland was. Charles, ever the comic, and having no idea, said, “No, but I can tell you it’s not on the Piccadilly Line.” We researched the kingdom and its cultural practices by borrowing a book from the library. By April 1968, with the paperwork done and me six months pregnant, we were ready to depart. Parry Harvey, the Swaziland National Assembly secretary, wrote to say that the job Charles had been offered had fallen through. We trusted in Bahá’u’lláh and departed a week later. John and Valera Allen, Knights of Bahá’u’lláh to Swaziland, were waiting for us at the airport in Lorenzo Marques (now Maputo), and we enjoyed a dusty two-hour ride in their stately American wagon to our new home. John and Val had settled in Swaziland in 1954 and became like parents to us – may God bless them both. We settled in Manzini, a dry hot lowveld town, where Charles found work and where, in July 1968, our second son Riccardo was born at the local mission hospital.

Helen Wilks was one of the beautiful souls living in Manzini along with Chuck and Serafina Ducker. When Helen was young someone told her that Jesus had returned. After some years of searching, travelling to feel the truth, she found it. This truth became her lifetime companion. She made different crafts, writing quotations on them, to give away, especially for the children. Iris Foster and Pat Hewitt, two brave souls, were also in Swaziland laying a foundation for the growth of the Faith. We had a loving Local Spiritual Assembly, and made lots of teaching trips to nearby villages. Swaziland was alive for teaching and with the help of a lovely translator we were blessed to be able to converse with those who spoke no English.

Dale was also back in Swaziland, with his wife Irma. Dale had two brothers who had moved back to the States, while he and Irma stayed on to run the family pineapple business. With their three boys they became lifelong friends with our family. Dale sadly passed away a few years ago following an accident at his parents’ home. Irma, charming as ever, continues to be active in the educational sector. Earlier this year we met up in Mbabane to reminisce on our nearly sixty years of loving friendship.

Swaziland is a beautiful country noted for its high peaks rich in minerals and tropical farmlands of sugar cane and pineapples. In the late 1960s, its lax apartheid and social laws attracted pleasure-seeking gamblers from its wealthy neighbour, South Africa. Relations across the colour bar and gambling were banned in South Africa. A consequence of Swaziland’s open social policy was destitution, vice, and unwanted pregnancies. Later, Swaziland was afflicted with one of the highest HIV rates in the world, leaving grandparents to care for grandchildren. But a light was ignited amongst this darkness. It was so uplifting when, years later, Irma took me to the prize-giving ceremony at a Bahá’í-inspired nursery school where the 85 children were accompanied by parents, mostly both parents. I thank Bahá’u’lláh a billion times for transforming the new generation of man and thank all those friends who worked hard to achieve it.

In 1967 the regional National Assembly of Swaziland, Lesotho, and Mozambique formed, emerging out of the National Assembly of South and West Africa, which had formed in 1956. Charles travelled a lot each day to Mbabane for work and occasionally drove to Lesotho to attend the regional meetings. Fortunately we were soon able to afford a second car, allowing me to travel to villages and communities around Manzini.

Swaziland was now blessed with an established Bahá’í community and our local efforts were reinforced during the early 1970s by frequent visits from Hands of the Cause. Pioneers from Iran and Malaysia began to arrive after independence from Britain in September 1968 when immigration laws were relaxed. Intense efforts building up to the end of the Nine Year Plan in 1973 led to many friends relocating to southern Africa. Hand of the Cause Dr Muhajir travelled repeatedly to southern Africa while also visiting Iran and Malaysia encouraging friends to move. The dear doctors Dr Ahmadi and Dr Khayyam settled with their families in Mbabane in mid 1972 alongside Masoud Ehsani, and Ravichandran came from Malaysia.

In August 1972, Ruhiyyih Khanum visited Swaziland during her epic three-year overland journey across Africa, meeting with the king and other dignitaries. She spoke at the dedication of the Leroy Ioas institute, which served as the National Centre and Temple Land. Amatu’l-Baha reminded us to treat all people equally and make all feel comfortable, irrespective of customs and traditions. Many friends asked why Bahá’ís should obey a government if we did not agree with its policies. Wisely she replied, “If we, who believe in unity, become involved in political factions and civil disorder, then where is the hope for a misguided society?”

The teaching work was going ahead successfully, with additional pioneers coming to the country. We were blessed with a third son, Charles, born in Mbabane in March 1972. I spent a lot of time walking in the fields visiting homes to deepen the new Bahá’ís. We loved our home in Manzini, but I developed an allergy to grass and my asthma would often flare up. Charles bought some land in the pre-mountains with a plan to grow eucalyptus trees. The leaves could be harvested for medicinal purposes and the trunks for telegraph poles. Charles was eager to obtain permanent residence status. But it was not to be. Two years into the project we were notified that our temporary residence permit would not be renewed. Charles was disappointed but Ben Dlamini, a fellow member of the NSA, said, “Charles this is not the government, it is Bahá’u’lláh.” Many thousands of little trees had to be abandoned and the land was eventually lost.

With three young children and with great sadness we packed our bags to leave our pioneering spot and our dear friends behind. Charles’ job was transferred to Johannesburg where immigration rules gave us six months to decide where to go. The apartheid system was littered with restrictions. One of these was a still uncertain process of how to treat Persians. Johannesburg had a few Bahá’ís scattered around and we so looked forward to weekly deepening meetings at the home of Bahiyyih Randall Winkler (Ford), the beloved Counsellor whose love and charm knew no bounds.

Anti-apartheid pressure was growing on the South African government. In early 1975 the government permitted the first public multi-racial gatherings. One venue in the country was approved for this purpose, the Holiday Inn near the airport. Lowell Johnson, the radio DJ with the smoothest of voices (his opening radio line being, ‘This is your DJ LJ’) and secretary to the National Assembly, quickly arranged a meeting. That unforgettable afternoon, seated at a ten-metre-long table, friends from all races, full of all the blessings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, joyfully shared fruit, nuts, raisins, dates, tea and uplifting conversation. Government rules, absurdly, did not permit hot food to be served at multi-racial gatherings. That day was a great teaching day.

Those months we prayed to be guided to choose a new home. We also enjoyed meeting new friends of all races and learning more about South Africa’s early believers and pioneers. From visits by Martha Root in the 1920s, to Agnes Carey, a social worker later titled ‘Mother of the Bahá’ís of South Africa’ by the Guardian, to the gifted artist Reginald Turvey, named by the beloved Guardian, ‘Father of the Bahá’ís of South Africa’. Dorothy Senne, a school teacher, was the first South African woman to become a Bahá’í. There was the arrival of the Sears and Robarts families in the 1950s, and the families of Malay and Indian descent who embraced the Faith in the late 1950s. And of course, Lowell Johnson, who dedicated over fifty years of his life to promoting the Bahá’í teachings while under constant surveillance by the authorities whose mandate was to maintain racial separation. Under these racial laws, we Bahá’ís had to walk a fine line when organizing meetings for worship and discussion as we were bound by the principles of our Faith to adhere to racial integration, and to remain obedient to the laws of the land. How marvellous that, in a land plagued by apartheid, the first national Bahá’í governing council, elected in 1956, had four white and five black members. We enjoyed meeting these new friends, and I reflect joyfully on the longevity of those friendships from the 1960s and 1970s.

We wrote to the Universal House of Justice seeking prayers and guidance on where our next home should be. They replied that we are free to go anywhere, but preferably to remain in Africa. Not long thereafter, dear Shidan Fatheazam, Counsellor for Southern Africa living in Salisbury (now Harare) invited us to a conference. It was our first trip to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), travelling through the industrial city of Bulawayo, and mightily impressed by the sheer magnificence of Victoria Falls. We knew little of the country, except that a minority white government had, in 1965, resisted the call for independence. And, as a result, the international community had placed sanctions of all sorts on the country.

European settlers were fleeing the country, predicting that the occasional skirmish would escalate to full blown civil war. Many indigenous Zimbabweans were exiting to receive military training. The conference we had been invited to was lovely and in mid-1975, desiring to stay in Africa, we found a new home in Bulawayo.

The racial laws were similar to South Africa’s, though not as harsh. Schools and suburbs were segregated, but the military was multi-racial. People needed jobs. International sanctions impacted every aspect of life. Fuel was rationed based on detailed calculations of distance from home to work and school, and fuel coupons were issued monthly. Travelling to rural villages or even across the city required careful planning.

Teaching the faith was a challenge. Christianity had a strong presence among less-educated persons, and many educated Zimbabweans focused more on liberation and politics than on faith. The small community in Bulawayo had a core group of friends, but teaching was difficult. Iran and Enayat Sohaili and their four children were close family friends. Canaan Ncube, Talita and Zapahnaya Ndlovu and Doreen Mpofu became lifelong friends. Over the next five years, the impact of sanctions and mass emigration exhausted the European settlers’ resolve. Rhodesia proudly became Zimbabwe, a free nation and a youthful democracy. Bob Marley sang to the crowds at the independence celebrations in April 1980.

Numbers gradually increased following independence. New pioneers arrived: Alan and Andisheh Dawson, and later Dicky Fusco and Evalie Heath. And with rising economic growth and educational standards, more indigenous friends joined the Faith. But again teaching became difficult due to prevailing social conditions. Bulawayo became a casualty of the growing regional and tribal tensions within the country. Since the late 1990s the city, now with over a million people, struggled for its survival, faring worse than the country as a whole.

Art gave me much pleasure. I loved drawing portraits and landscapes. To give my art a social purpose I took to making sculptures, generally out of metal. Life-size images depicting the unity of mankind or the equality of men and women were donated to public places. Two were placed in local parks. A statue depicting a man reading was donated to Mpopomo Library; another depicting ‘work is worship’ to Nkulumane Clinic. Twenty-five years later I returned to see them in a poor state, most of the metal stolen. A sign of the desperate poverty plaguing this beautiful, rich country.

Charles had been unwell since his 40s, with kidney problems and poor circulation which led to him losing a limb in 1990, and later cancer. But his warm and loving spirit never left him. All three children eventually left Bulawayo, settling in the UK and Australia. We enjoyed our later years in the slow pace amongst the gentle people of this nation. We became tuned to the cycles of drought, hyperinflation, sporadic supply of running water and electricity, and a government with seeming disregard for its own peoples. Hyperinflation around 2010 resulted in currency bills with sixteen digits. A wheelbarrow of notes was worth less than the barrow itself. Bank notes were printed so rapidly and on such a meagre budget that one side was left blank and the ink was still wet when circulated. Sheer desperation. We so looked forward to a couple of summer months in Europe each southern winter. In addition to visiting family and friends in the UK, we would endeavour to link up with teaching projects in eastern and southern Europe making, along the way, many good friends in Croatia, Malta and Bulgaria. Charles sadly passed away in 2012 just shy of his 77th birthday, following surgery in Johannesburg.

As I reflect on a long life I am grateful for all the wonderful souls who have accompanied me on my journey. From my early childhood in Iran where my father chanted and Uncle Jacoub dreamed, to the awakening that a life of pioneering and service to others brings incredible joy but also sacrifice, to my immediate family and wonderful friends spread across the world, but especially those in southern Africa, my home since 1968. All of these beautiful people and places have enriched my own spiritual awakenings, convictions and blessings. I pass each day thankful for God’s small mercies.

Bahiyeh Caprez

May 2025, Zimbabwe

Bahiyeh sadly passed away on 6 January 2026

Fascinating! A wonderful account, beautifully written, of a life dedicated to the Faith. Truly inspirational.

Such a beautifully rich and well written account full of references that would be unknown otherwise. Thank you for this write up. My awakening to the faith is strongly connected to knowing Charles and Soraya at English summer schools. Their dedication to teaching and purity of heart had a big effect on me. I will never forget how Soraya chose to cut her own hair as she was so conscious of the needs of the faith , and would redirect the money she saved by not using the hairdressers.

Thank you, dear Soraya, for writing this very interesting story of your life as a Bahá’í in Iran, the United Kingdom, and Africa.

What wonderful service to the Faith you and Charles have given over the years! What you have written is immensely interesting Bahá’í history and it is a beautiful record of dedication to the Faith over many decades.

Of course you have also been blessed to have met so many of the Hands of the Cause. Very special times indeed!

Ron and I used to look forward to your regular visits to summer schools in the UK when he and Charles especially would enjoy each other’s company.

Reading this history on the day of Soraya jan’s passing made her life story even more special as I didn’t knew her beautiful life memories in such details. But living in Bulawayo for few years (1979-1982) Soraya jan and Charles were our dear friends/family members. So glad Paul Caprez mentioned about Baha’i History site and reading it and remembering Soraya jan. We (Doreen Mpofu, Andisheh Taeed, my sister and I), were over joyed on 18 August 2025 to have Soraya jan visit us in Taunton for an afternoon with her dear sister and Charles, her youngest son.

Offering prayers tonight in her memory and asking consolation for her dear family at this hard time of separation 🙏🌷 Helga Taeed